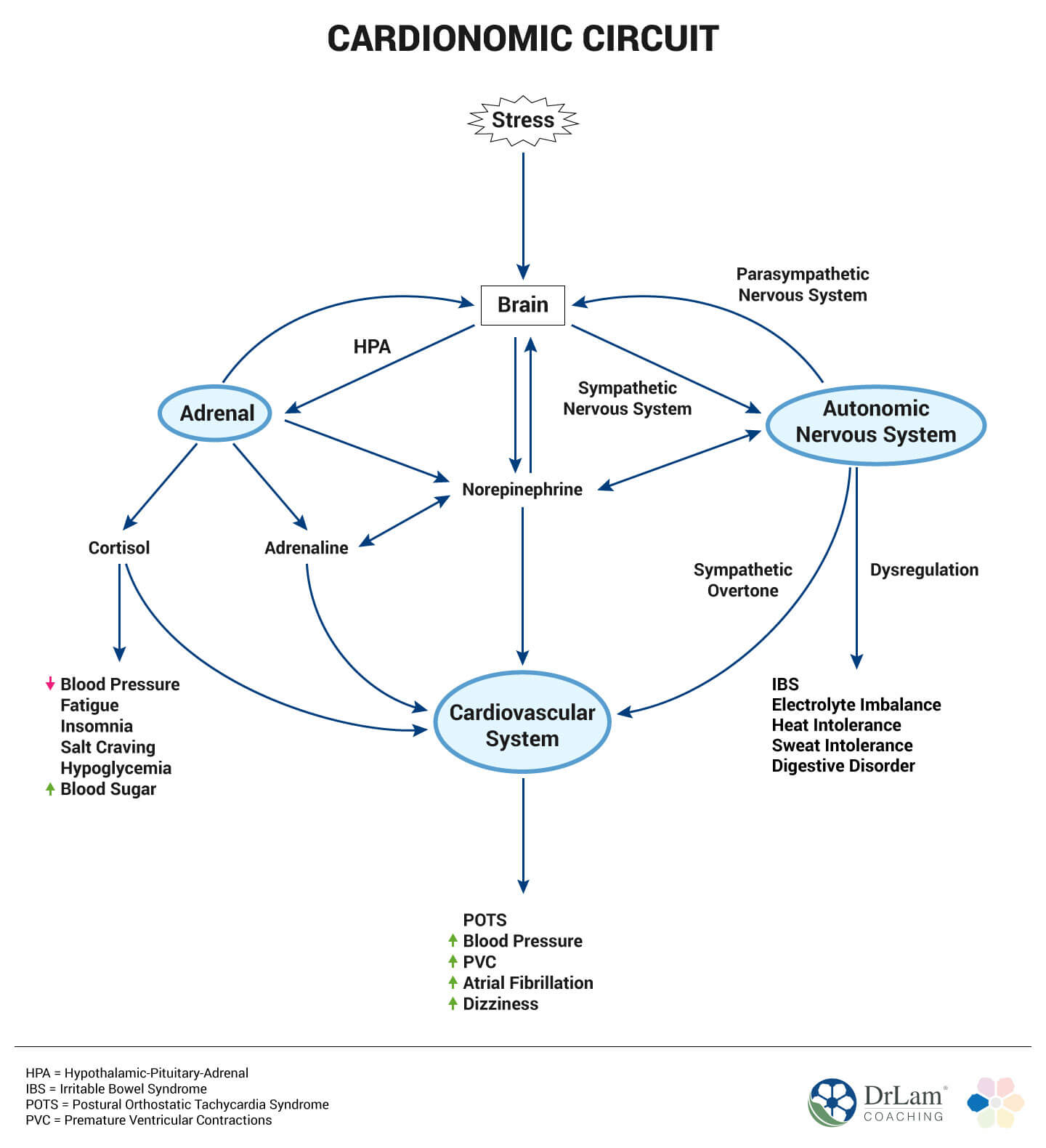

Our body's overall approach to stress regulation is through the NeuroEndoMetabolic (NEM) stress response apparatus. There are two major components to this: a conventional neuroendocrine component and a functional metabolic component. Only by combining the two halves can a holistic view of the body's stress response be seen and evaluated comprehensively. By incorporating the metabolism component which is systemic in nature into the traditional neuroendocrine stress response equation, which is mostly organ-specific, we see how the body uses both localized organ specific responses as well as systemic responses, such as the cardionomic circuit, to overcome stress from a functional perspective.

Our body's overall approach to stress regulation is through the NeuroEndoMetabolic (NEM) stress response apparatus. There are two major components to this: a conventional neuroendocrine component and a functional metabolic component. Only by combining the two halves can a holistic view of the body's stress response be seen and evaluated comprehensively. By incorporating the metabolism component which is systemic in nature into the traditional neuroendocrine stress response equation, which is mostly organ-specific, we see how the body uses both localized organ specific responses as well as systemic responses, such as the cardionomic circuit, to overcome stress from a functional perspective.

The two components are organizationally broken down into six circuits each in the body: hormone, cardionomic, neuroaffective, metabolism, detoxification, and inflammation. All six of these circuits work in unison to handle stress. Organ systems within the neuroendocrine circuits involve the thyroid, adrenals, cardiovascular system (CVS), autonomic nervous system (ANS), central nervous system (CNS), and the GI tract. The cardionomic circuit falls within the neuroendocrine component but has important functional properties systemically as well. The organ-system triad responsible for controlling the cardionomic circuit consists of the adrenal glands, CVS, and ANS.

Activation of the cardionomic circuit starts when stress arrives on our doorstep. Starting at the brain and ending at the adrenal glands, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) hormonal axis is the first responder and main conduit that regulates our body's everyday stress response. At the adrenal glands, cortisol output rises and acts as the body's primary de-stressing hormone.

The cardiovascular system (CVS) and the autonomic nervous system (ANS) parts of the cardionomic circuit are also activated but largely placed on standby when stress is mild. It is only put on full throttle when stress is severe and cortisol output falls. This usually occurs after extended stress beyond our adrenal glands ability to handle, resulting in falling cortisol output. Clinically, we call this the state of adrenal exhaustion (also called stage 3 Adrenal Fatigue Syndrome).

Therefore, the activation of the triad responsible for this circuit is progressive and tiered accordingly to the level of stress perceived. In other words, when stress is mild, not all parts of the triad need to be fully activated. The HPA hormonal system alone targeting the adrenal glands is sufficient to help the body deal with stress through the hormone cortisol. When stress is severe or chronic, the body may need more assistance.

As needed, the CVS and ANS become fully activated and more prominently deployed in addition to the existing HPA hormonal axis.

Having three parts (the triad) working seamlessly together as one interconnected circuit balances the workload and prevents overuse of any one system (which can lead to dysfunction). Each part of the circuit is therefore called upon on an “as needed basis” as the body sees fit and they work synergistically with each other in a well-orchestrated progression.

We use the term cardionomic circuit dysfunction (CCD) to describe a perfect storm where all three parts of the cardionomic triad (CVS, ANS, and the adrenals) malfunction or become dysregulated concurrently. There can be devastating clinical consequences that are incapacitating when this occurs.

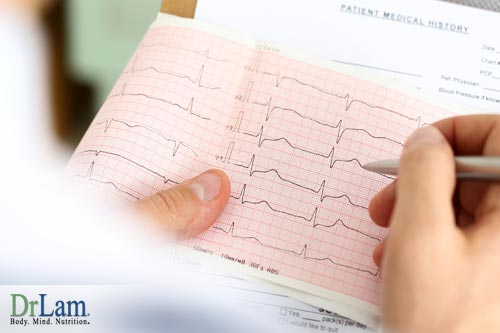

When CCD occurs, there also tends to be stepped progression of this systematic breakdown. Initial overload and eventual dysregulation of the first responder HPA hormonal axis that regulates adrenal function and cortisol output is usually the first thing to go wrong. With this comes metabolic imbalances such as exercise intolerance, sugar craving, hypoglycemia, and fatigue. The sympathoadrenal hormone system (SAS) of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), which regulates norepinephrine and epinephrine (also called adrenaline) output, is next functionally in the progression to be dysregulated. Anxiety, rapid heart rate, subclinical POTS, and insomnia are representative symptoms. Dysfunction progression affecting the CVS leads to damage of cardiac nodes (or “spark plug” of the heart that regulate heartbeats) are the last to fail. This results in PVCs, atrial fibrillation blood pressure instability (such as postural hypotension), and idiopathic supraventricular tachycardia.

When CCD occurs, there also tends to be stepped progression of this systematic breakdown. Initial overload and eventual dysregulation of the first responder HPA hormonal axis that regulates adrenal function and cortisol output is usually the first thing to go wrong. With this comes metabolic imbalances such as exercise intolerance, sugar craving, hypoglycemia, and fatigue. The sympathoadrenal hormone system (SAS) of the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS), which regulates norepinephrine and epinephrine (also called adrenaline) output, is next functionally in the progression to be dysregulated. Anxiety, rapid heart rate, subclinical POTS, and insomnia are representative symptoms. Dysfunction progression affecting the CVS leads to damage of cardiac nodes (or “spark plug” of the heart that regulate heartbeats) are the last to fail. This results in PVCs, atrial fibrillation blood pressure instability (such as postural hypotension), and idiopathic supraventricular tachycardia.

Therefore, cardiac arrhythmias and vascular dysregulation are reactive consequences of the CVS's response to stress. They tend to be late ramifications, but once symptoms surface, major disruptions to the cardionomic system and destabilization of the entire body can occur. This also means that different parts of the triad contribute differently to the overall stress defense mechanism and different symptoms with each level of dysfunction warn us of different degrees of danger within the system.

The speed of decline usually is gradual and can occur over years or decades. Symptoms are mild at first, such as occasional stress (either physical or emotional) related heart pounding, dizziness, breathlessness, high blood pressure, and heat intolerance. As CCD progresses, more debilitating symptoms such as postural orthostatic tachycardia (POTS), PVCs, atrial fibrillation, adrenaline rush, severe and chronic insomnia, and panic attacks surface. A person can be bedridden and rendered a cardiac cripple at the end. In rare occasions, CCD can also occur acutely, such as during an acute traumatic accident, during antibiotic therapy, after over exercise, or through extreme emotional stress.

When faced with stress, the body's primary function above all else is to maintain the survival of our species. The three main hormones responsible for regulating the cardionomic circuit are cortisol, norepinephrine, and epinephrine.

Cortisol, a glucocorticoid (or steroid hormone), is produced from cholesterol by the adrenal glands. It is considered the body's primarily anti-stress hormone. Mental stress has been tied to enhanced platelet aggregation as well as the rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque and subsequent thrombosis. This can lead to coronary artery occlusion and heart attack, which in some cases may contribute to sudden death.

Cortisol is released from the adrenal glands in response to normal daily activities such as waking up, exercising, and acute stress. It helps the body overcome stress by providing the right nutritional substrates for energy production.  Cortisol helps select the right type and amount of nutrient (carbohydrate, fat, or protein) for fuel needed by the body to produce energy to keep the heart pumping properly to meet the increase in oxygen demanded by stress.

Cortisol helps select the right type and amount of nutrient (carbohydrate, fat, or protein) for fuel needed by the body to produce energy to keep the heart pumping properly to meet the increase in oxygen demanded by stress.

When released from the adrenal gland, cortisol enters the circulatory system immediately. Vascular tone is increased, leading to constriction of blood vessels in order to increase blood flow. Cortisol fills the blood with glucose to be used by our skeletal muscles while insulin is restricted. Thus, cortisol decreases hypoglycemia from a metabolic perspective as well.

Cortisol's effect on the cardionomic system is great. It allows quick energy to be produced by the mitochondria of cardiac muscle as glucose is used rather than stored. The heart needs to pump harder in times of stress relative to normal daily living, and cardiac workload demand increases. A state of hypertension may result, as well as increased risk of coronary heart disease when cortisol level is chronically high. This has been well documented in numerous studies showing increased work stress with an increased incidence of cardiovascular risk. Cortisol appears to be the key link to this cascade. Providing more evidence to this link is clinical evidence that those with Cushing's Syndrome have higher endothelial damage compared to healthy people. While a normal cortisol level is required for optimum health, excess cortisol, as happened when the HPA axis is on overdrive to deal with stress, is associated with increased heart rate, increased level of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), fasting insulin, and serum glucose. In turn, this leads to higher risk of adult onset diabetes mellitus (AODM). Despite cortisol's well know anti-inflammatory properties, studies have shown that dysregulated cortisol secretion (too high or too low) may involve a failure to contain inflammatory activity.

There is a limit to cortisol's anti-stress action. When exceeded, the body has no option but to ring the alarm bell for more help. This leads to the activation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) as the next level of defense, where the hormones norepinephrine and epinephrine are released.

This chemical belongs to a class of powerful stimulatory compounds called catecholamines. Norepinephrine is both a neurotransmitter and a hormone. Inside the brain, norepinephrine causes localized alertness mentally to keep us on the lookout for danger ahead. We tend to stay awake and “wired”. Multiple street drugs are derivative of this compound and designed to achieve a “high” feeling.

Norepinephrine also behaves as a hormone outside the central nervous system. It travels as a hormone as part of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), targeting the heart. Once arrived at its destination, norepinephrine triggers excitation responses from cardiac nodes (or “spark plugs”) and muscles of the heart. The more norepinephrine in the heart, the harder the energy factor of each cardiac muscle fiber has to work. This leads to a higher resting heart rate and stronger pulse.

One cannot stand up from a supine position without some level of norepinephrine in our cardiovascular system. It is, therefore, essential for healthy normal living. Only when it is excessive do we get into trouble. Remember that normal people generally do not feel their heart beating during daily living. Too much norepinephrine in our body (technically called reactive sympathetic overtone, also known as adrenaline dominance) can cause havoc within. Inside the brain, excessive norepinephrine triggers anxiety and panic attacks, insomnia and nightmares. At the heart, norepinephrine overload results in a heart that is pounding strong or “falling out”, as some would report.

One cannot stand up from a supine position without some level of norepinephrine in our cardiovascular system. It is, therefore, essential for healthy normal living. Only when it is excessive do we get into trouble. Remember that normal people generally do not feel their heart beating during daily living. Too much norepinephrine in our body (technically called reactive sympathetic overtone, also known as adrenaline dominance) can cause havoc within. Inside the brain, excessive norepinephrine triggers anxiety and panic attacks, insomnia and nightmares. At the heart, norepinephrine overload results in a heart that is pounding strong or “falling out”, as some would report.

Norepinephrine, along with cortisol, are the dynamic duo that helps the body handle most stressors on a day to day basis. They may not be sufficient if severe stress is present or perceived to be on hand. For fast and immediate emergency stress relief action, epinephrine is the hormone of choice.

Epinephrine is a hormone released by the adrenal medulla in response to direct command from the brain via the adrenomedullary hormone system (AHS), one of 5 branches of our ANS. It is by far the most potent of all stimulating hormones in our body and only releases in large amounts as a last resort by the body when survival is threatened. It is largely responsible for our “flight or fight “ response as it prepares the body, especially the heart and skeletal muscle, to run away from physical danger. Rapid increase in heart rate is a key result. With more beats per minute, we are able to pump out more blood from the heart which will, in turn, help oxygenate our skeletal muscles to contract and allow us to run away from danger. Excessive epinephrine, however, is destabilizing and can ruin your life.

Epinephrine's effect on the heart rate control is immense. Cardiac nodes are a concentrated conglomerate of the nerve conduction network inside the heart that regulates electrical conduction and thus heart rate. They work like spark plugs of an automobile. They fire on a regular basis, properly timed to allow adequate filling of blood into the heart and its ejection to the periphery. Normal heart rate is around 70 beats per minute. A heart rate that is excessively fast –triggered by too much adrenaline – reduces filling time and results is less cardiac output per beat. Peripheral circulation is compromised. Blood pressure can be unstable. One can feel dizzy in such conditions.

Nodes that are constantly bathed in adrenaline can eventually be over stimulated and damaged. Like a light switch being turned on and off too often without adequate rest, breakdown occurs. When that happens, the heart starts to beat irregularly. Supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, postural orthostatic tachycardia (POTS), idiopathic sinus tachycardia, and PVCs are some commonly encountered conditions when the heart's firing mechanism is dysfunctional.  Excessively fast heart rate also generates unwanted reactive metabolites at the cellular level, which in turn are abrasive to the cardiac nodes due to their inflammatory effect and causes a vicious decompensatory positive cycle that is ultimately destabilizing.

Excessively fast heart rate also generates unwanted reactive metabolites at the cellular level, which in turn are abrasive to the cardiac nodes due to their inflammatory effect and causes a vicious decompensatory positive cycle that is ultimately destabilizing.

It should be clear that while these three key hormones modulate the cardionomic circuit, the physiological ramification of their dysregulation can have negative systemic effects well beyond the heart. That is why a body in CCD is in great turbulence. Symptoms are systemic in addition to localized. The entire body is at risk.

All 6 NEM response circuits are at play in times of stress automatically. Multiple organs and systems are therefore involved. Some symptoms are directly traceable to the cardionomic circuit, while others are an indirect effect of the triad in trouble. Based on the degree of circuit damage, one can experience a full spectrum of patient complaints ranging from mild annoyances to severe incapacitation.

Most of the symptoms presented with CCD are driven by the adrenal glands and ANS. The cardiovascular system plays an important role – being the alarm in the triad. Instead of being a driver of symptoms from the back end, it is on the front end of the clinical presentation. In other words, clinical presentations are mostly based on CVS dysfunction such as dizziness, blood pressure and rate irregularity, and cardiac arrhythmias. These are symptoms that bring sufferers to their doctor. The underlying drivers are cortisol, norepinephrine, and epinephrine.

Symptoms include:

Not everyone will exhibit all the symptoms at the same time. The intensity also varies greatly from person to person. Usually, a few symptoms are more prominent than others, depending on the body's constitution and state of weakness. This is why identifying CCD as the root cause is challenging. Clinicians not on the alert for a cardionomic circuit factor often focus only on organs and systems representing symptoms on hand. Extensive cardiac, endocrine and neurological work are usually conducted. Most are given a clean bill of health when symptoms are mild. Yet sufferers have multiple complaints that tend to be fleeting in nature.

Maintaining strong cardiac output while protecting our heart from excessive wear and tear is an important defense mechanism. This is accomplished by the sequential tiered release of the three cardionomic hormonal modulators mentioned above.  The CVS provides the final safety-valve and necessary feedback signals to alert us if the ANS or adrenal glands are overloaded. Homeostasis is thus achieved. Depending on each person's constitution and state, undesirable symptoms of dysfunction can range from mild annoyances to incapacitating symptoms so immense and overwhelming that tend to have no apparent logical flow.

The CVS provides the final safety-valve and necessary feedback signals to alert us if the ANS or adrenal glands are overloaded. Homeostasis is thus achieved. Depending on each person's constitution and state, undesirable symptoms of dysfunction can range from mild annoyances to incapacitating symptoms so immense and overwhelming that tend to have no apparent logical flow.

Symptoms of CCD can be fleeting in nature, reflective of an underlying hormonal imbalance. When CCD is mild, symptoms tend to be on occasion or come and go with varying frequency and severity. When CCD is severe, symptoms wax and wane with great variation in timing, intensity, and severity. In such clinical state, the body appeared to have lost its ability to fine tune its self-regulatory mechanism. Symptoms can include random onset of anxiety followed by subsequent depression, being wired and tired at night, extreme episodes of fatigue interspersed with burst of energy, panic attack followed by depression, energy slumps in the early afternoon followed by energy bursts later, paradoxical and hypersensitivity reactions to dietary supplements that may disappear from time to time only to resurface, heart palpitations that come on at rest or during exertion without predictable fashion, and constipation alternating with diarrhea. On the surface, it appears that the adrenals are in disarray, the autonomic nervous system is unstable, and heart is “acting up”.

On deeper examination, however, a different picture can emerge. Let us not forget that hormones modulating the cardionomic circuit are not equal in potency, velocity, or volume of output when activated. The ultimate clinical presentation represents the entire sum of these hormones at the cellular level along with actions of the other five NEM stress response circuits. Chaos may appear superficially, but the body in effect behaves logically. Let us see how.

Of the three main hormones modulating the cardionomic circuit, epinephrine is physiologically the most “potent”. Epinephrine is a fast acting hormone with a short half life by design. Next in potency is norepinephrine, and finally cortisol.

In times of severe stress, epinephrine output from the adrenal glands goes up, and its metabolization rate goes down. These two tracks working together leads to a larger pool of epinephrine in the body with very short notice. Symptoms driven largely by epinephrine (such as panic attack and atrial fibrillation) tend to surface at the forefront. Symptoms driven by norepinephrine (such as heart pounding and insomnia) and cortisol (hypoglycemia and immune system dysregulation) retreat to the background on a relative basis when epinephrine floods the body. In the absence of epinephrine overload, norepinephrine driven symptoms become more dominant.

Cortisol is the more gentle and slower acting hormone on the cardionomic circuit, when compared to norepinephrine and epinephrine. Cortisol acts simultaneously as both a gentle acceleration and breaking system on the heart to increase sugar delivery to the mitochondria (as fuel for ATP generation), while reducing inflammation that can potentially damage the intracellular mitochondrial function of excessive reactive metabolites from stress.  It helps the body deal with the stress of daily living but is not the hormone of choice the body relies on in times of severe or acute stress. For that, it relies first on norepinephrine, and ultimately, epinephrine. Cortisol driven symptoms, therefore, tend to be very subtle.

It helps the body deal with the stress of daily living but is not the hormone of choice the body relies on in times of severe or acute stress. For that, it relies first on norepinephrine, and ultimately, epinephrine. Cortisol driven symptoms, therefore, tend to be very subtle.

It is important for us to know that all three hormones are released in time of stress. The body does not take any chances. The key regulation lies in the amount of each released and their timing. At times of mild to moderate stress, cortisol along with norepinephrine are both released to enhance the pumping action of the heart, thereby increasing cardiac output per beat. These two work in unison to increase blood flow and provide fuel for cellular metabolism. This leads to an increase in energy production to the rest of the body, especially the brain and skeletal muscles, in times of stress. Under most mild to moderately stressful situations, these two hormones working together are sufficient to handle and neutralize stress. One may feel a bit “stressed out” at times but return to normal function within a short time.

Epinephrine, being the most potent anti-stress hormone, is highly regulated. Its output is also tightly controlled. Only when cortisol and norepinephrine are insufficient to normalize stress will the AHS system be put on full throttle, thereby flooding the body with epinephrine. Because epinephrine is an extremely potent vasoconstrictor, its presence signals a state of emergency, and its power often overwhelms the rest of the body's hormones. This is the way our body is designed because adrenaline is the hormone of last resort. This is the last bullet in the arsenal against stress. There are also no physiological compounds or hormones to oppose epinephrine by design. Once released, it has to be cleared out of the body by metabolic pathways which take multiple steps and time. This is why it is so important that epinephrine is only activated as a last resort and only in large amounts in an emergency. Improper function or dysregulation of adrenaline output can ruin your body otherwise.

Lastly, remember that cortisol, norepinephrine, and epinephrine are released into our bloodstream and cleared out of the body in different velocities. This is an important fine tune regulatory mechanism. The amount of each hormone within us therefore varies. The body can go through peak and valley cycles.

When one hormone is at its peak, such as epinephrine, the other hormonal modulators take a back seat. On the reverse, when epinephrine output is at a low, the backseat hormones resurface and exert overall control. This allows each modulating hormonal system the proper rest and repair. Depending on the dominant hormone in charge at each particular point in time, we see different symptoms being dominant. Dominance can be fleeting and vacillating. Clinicians not on the alert for this will find it hard to manage a body that seems to be a moving target with a chaotic presentation.

Symptoms that are fleeting in nature are therefore a normal physiological response under most circumstances. The body is in charge and there is a logical progression to its reactions. Few understand because cardiac arrhythmia can be very scary.

Symptoms that are fleeting in nature are therefore a normal physiological response under most circumstances. The body is in charge and there is a logical progression to its reactions. Few understand because cardiac arrhythmia can be very scary.

Most experiencing this rightfully head towards the emergency room. Often they are discharged to go home and relax after a normal cardiac workup. In severe cases of CCD, a cardiology workup would be conducted and a diagnosis called dysautonomia is often given.

Dysautonomia is a term for a collection of diseases that arise from malfunction of the ANS. It may be due to inherited or degenerative neurological (primary dysautonomia) or it may arise due to damage of the autonomic nervous system from an acquired disorder (secondary dysautonomia), such as diabetes, MS, HIV, autoimmune disease, Lyme disease, or spinal cord injury.

Conventional medicine seldom considers stress and subsequent CCD as the common underlying pathogenesis of both primary or secondary dysautonomia, even though SNS predominant dysautonomia is often associated with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and interstitial cystitis. The entire investigation is often focused in on a specific organ or system dysfunction.

To properly evaluate dysautonomia from a functional perspective, it is important to resist the temptation to micro-analyze each symptom but focus on the big picture of what the body is trying to tell us. The big picture perspective is clear when CCD driven dysautonomia is involved. The body is not happy nor calm. It is in a state of general anxiety, easily irritable, with heart palpitations? when under stress, waking up in the middle of the night with fast or strong heart rate, and unable to return to sleep after awakening. Sometimes adrenaline rush could follow a biological circadian rhythm, especially in the morning. It can be triggered by low blood sugar or imbalanced cortisol. There can be a convoluted history going back years that may include: low immune state, insomnia, low libido, emotional stress, excessive physical exertion, chronic infection, gut problems, or excessive antibiotic exposure.

From afar, a body with CCD driven dysautonomia is irritable and easily excited. Triggers as minor as a small argument to a longer than usual car ride, excessive exercise, watching an action movie, exposure to cold wind, and a diet high in sugar. The body is fragile, always ready to throw a “temper tantrum” without apparent notice or at the slightest deviation away from daily routine. A sense of impending doom can be great, with frequent visits to the emergency room only to be told all is well.

The take-home lesson is simple. Dysautonomia that is pure and organic in nature presents with a strong cardiac component such as arrhythmia but little other systemic symptoms. Stress-driven dysautonomia has a much broader systemic presentation clinically in addition to cardiovascular and autonomic dysregulation.

A detailed history will likely show a body burdened with:

The collective picture is a body in NEM Response Exhaustion (stage 3 of the NEM stress response continuum) or worse.

Routine workups are usually unremarkable. Invariably, the cardiac workup is normal, neurotransmitter studies are normal or borderline high, and physical examination is unremarkable. A tilt table test for POTS may be positive or normal, and thus most are diagnosed as having dysautonomia. Salivary Alpha amylase may be elevated. Neurotransmitter studies may show normal or high dopamine, norepinephrine and epinephrine. ACTH test for Addison's Disease is unremarkable. Sleep studies usually show a lack of deep sleep, but either borderline or no obstruction. Serum electrolytes are normal, as well as gastroscopy, colonoscopy, and fecal studies. Four-point saliva cortisol may show high morning cortisol with the rest of the day being normal when symptoms are mild to moderate. A “flat” cortisol curve throughout the entire day is expected when symptoms are severe. Testosterone and DHEA levels may be low. Vestibular studies are normal. Methylation pathways may show positive MTHFR and pyroluria defects. Acupuncture and neurofeedback can be helpful temporarily but also can worsen the condition. Advanced functional medicine studies may show high CRP and sIgA.

Treatment from the conventional medicine perspective is often focused on organ-specific symptoms patching.

It can include the following:

Without factoring in stress-induced CCD as the cause, treatment is usually initiated with symptom-patching prescription medications. In particular, the premature use of beta-blocker for modulating electrical conductivity to lower resting heart rate can be problematic long term, even though there may be short-term relief. Suppressing an elevated resting heart rate or postural tachycardia may appear medically logical using such medications.

Unfortunately, they generally fail over time and instead worsen the condition because the heart develops collateral electrical conduction pathways when the primary ones are suppressed.

The heart, in particular, is an organ that has multiple redundancy pathways for rhythm and rate control. When one electrical conduction pathway is suppressed by medication (such as with beta-blockers), alternative less robust and primitive pathways will be automatically activated. These are reserved pathways designed for short term emergency use as a natural backup system. They are not intended to be permanent fixes. Suppressing primary pathways may reduce heart rate, but increase the risk of ectopic beats and rhythm over time.

In addition, stronger dosages are often needed to achieve the same clinical result over time as the body develops tolerance and resistance to medications. The more the cardionomic circuit is dysfunctional from over suppression of normal electrical conduction pathways, the more fragile and sensitive the heart can become over time. The more sensitive the heart becomes, the lower the threshold it will take to trigger irregular heart rhythm and ectopic beats. Stress, sugary drinks, caffeine beverages, being exposed to cold air, over exercise, excessive carbohydrate meals, gluten, food sensitivities, chemicals, dairy products, and wheat are just some of the many triggers that can cause heart rate irregularity. Multiple visits to the emergency room are common. Most are released to go home after an extensive cardiac workup.

In addition, stronger dosages are often needed to achieve the same clinical result over time as the body develops tolerance and resistance to medications. The more the cardionomic circuit is dysfunctional from over suppression of normal electrical conduction pathways, the more fragile and sensitive the heart can become over time. The more sensitive the heart becomes, the lower the threshold it will take to trigger irregular heart rhythm and ectopic beats. Stress, sugary drinks, caffeine beverages, being exposed to cold air, over exercise, excessive carbohydrate meals, gluten, food sensitivities, chemicals, dairy products, and wheat are just some of the many triggers that can cause heart rate irregularity. Multiple visits to the emergency room are common. Most are released to go home after an extensive cardiac workup.

Heroic measures with medications have their place. In an acute situation, they can indeed be life-saving. The key is to avoid starting such medication prematurely without exhausting all other natural or lifestyle approaches - unless there is absolutely no choice. It is easy to embark on medications but very difficult to get off. Once started, most stay on for life. Over time, as stronger and more medications are prescribed to achieve the same clinical outcome, the sufferer tends to worse gradually and deteriorate. This may take years or decades. Any attempt to reduce or stop medications can make matters worse.

Attempts to compartmentalize symptoms into disease entities helps the physician to isolate symptoms so they can be identified and patched. Without a holistic approach, however, the underlying root cause often goes unattended. Unless the root cause is resolved, suppression of symptoms can bring temporary benefit, but seldom produces long-term positive clinical outcome if CCD is involved. Let us look at how natural medicine approach may be different.

From a natural medicine and functional perspective, cardionomic circuit dysfunction represents symptoms of an underlying problem - a hyperactive autonomic nervous system along with HPA axis overdrive in the adrenal glands and reactive cardiac response of the firing nodes in the heart. This combination of insults forms a perfect storm. The heart is behaving as it should, reacting to stimuli as it should and sending us signals of its displeasure - alerting us to take corrective action to rid of the root problem. Unfortunately, cardiovascular system dysfunction can be life threatening and cannot be taken lightly. Arrhythmias represent the reactive response that once triggered, can take on its own course. Some arrhythmias are best to be left alone as they tend to resolve spontaneously, while others require medical intervention. For the sake of safety, most CCD sufferers are quickly placed on cardiac medications to stabilize heart rate. Long term considerations tend to take a back seat.

By the time CCD literate physicians are sought (usually out of desperation) most sufferers are already in an advanced state of weakness. Most are in NEM Response Exhaustion (stage 3) or approaching NEM Response Failure (stage 4). Many are housebound and on multiple medications. It is important to note that when the cardionomic circuit is dysfunctional?, the triad controlling this circuit can become very sensitive to external stimuli. The threshold that triggers paradoxical response, exaggerated response, and hypersensitivity reaction is very low.

Natural compounds with cardiac metabolic enhancing properties including CoQ10, lipoic acid, vitamin C, carnitine, hawthorn, and magnesium may not be well tolerated and in fact, can worsen the condition. Mineral supplementation and B vitamins could trigger adrenal crashes. Chelation of toxic or heavy metals may be mistakenly considered as removal of the “smoking gun”.

Natural compounds with cardiac metabolic enhancing properties including CoQ10, lipoic acid, vitamin C, carnitine, hawthorn, and magnesium may not be well tolerated and in fact, can worsen the condition. Mineral supplementation and B vitamins could trigger adrenal crashes. Chelation of toxic or heavy metals may be mistakenly considered as removal of the “smoking gun”.

Unfortunately, this seldom works long term. Functional medicine physicians may even be drawn into making a diagnosis of mitochondrial disease, but attempts to kick start the mitochondria may backfire and trigger arrhythmia and other side effects. Methylation enhancement likewise often fails even though genetic studies may support such approach. Physicians not used to dealing with such a sensitive body often find themselves not knowing what to do in such cases.

Cardionomic dysfunction symptoms, therefore, represent the body's cry for help. It is not a disease in and of itself unless there is an organic structure problem with the adrenal glands such as Addison's disease, primary dysautonomia, or a heart that is structurally damaged. Unfortunately, few physicians are on the alert to recognize such stress-driven CCD as part of the differential diagnosis.

Instead of rushing to prescribe medications or nutritional support, the first step of assessment should be focused on tracing the symptoms to their respective root causes. Establishing the right clinical descriptive is the most important key to recovery.

A detailed history along with real-time qualitative challenges over time are needed to evaluate the level of dysfunction the cardionomic circuit is in. This is a tedious process, requiring significant clinical experience and time. A blueprint for recovery needs to be constructed based on each person's needs. It necessarily has to be very comprehensive and systematic in approach. Each person is very different. There is no “one size fits all “ approach. Consideration of all six NEM stress response circuits and their interaction with each other is a must. Also needs to be factored in include the sufferer's constitution, sensitivity, current medication and supplements, nutritional reserve, and level of resilience.

Even in the best of hands, some trial and error is needed. Allow time for a slow and steady improvement, with provisions for set back. Too abrupt a change can throw the body into further imbalance and worsen the clinical state.

Managing expectations and educating the sufferer is very important to avoid clinical failure. The road to recovery is long. Attempts to shortcut the recovery process can backfire and worsen the existing condition.

The following can be considered to restore cardionomic balance over time in a systematic fashion, provided that it is individualized for each sufferer. Proper timing is critical. The right thing done at the wrong time can worsen the body.

A body with cardionomic circuit dysfunction is a sensitive and fragile one from a clinical perspective. Make no mistake about that. The smallest change in lifestyle, food, supplements, and medication can trigger further circuit dysfunction. It is critical to do the right thing at the right time. This is not a body that is healthy with occasional heart palpitations? that go away with rest. Sufferers are usually homebound, bedridden, or near end stage NEM response failure.

Self-navigation is not recommended. With proper repair and support, this circuit does have the strong ability to self-heal. The road to recovery is long, but worthwhile to avoid being a cardiac cripple for life. The younger and stronger the body, the greater the chance for recovery success. If you are concerned about your Cardionomic Circuit, don't leave your health to chance. Call us now at +1 (626) 571-1234 and let our dedicated professionals guide you on the path to a successful recovery.