The thyroid is an endocrine gland shaped like a butterfly. It is around two inches long and less than one ounce in weight. The gland is located in the front part of the neck, at the base, below the thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple), and it is made up of two lobes connected by a thin strip of tissue called the “isthmus”. Each lobe lies on one side of the trachea. The thyroid can be affected by different conditions that cause either hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Hypothyroidism is when the thyroid is underactive. Signs of hypothyroidism include tiredness, dry skin, thinning hair, and constipation. It is a very common condition, and it affects more women than it does men.

The thyroid is an endocrine gland shaped like a butterfly. It is around two inches long and less than one ounce in weight. The gland is located in the front part of the neck, at the base, below the thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple), and it is made up of two lobes connected by a thin strip of tissue called the “isthmus”. Each lobe lies on one side of the trachea. The thyroid can be affected by different conditions that cause either hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Hypothyroidism is when the thyroid is underactive. Signs of hypothyroidism include tiredness, dry skin, thinning hair, and constipation. It is a very common condition, and it affects more women than it does men.

Hyperthyroidism is the opposite; it is when the thyroid is overactive and produces an excess of thyroid hormones. Symptoms include hyperactivity, sensitivity to heat, hair loss, anxiety, irritability, and trembling.

Statistically, it is estimated that around 20 million Americans have a known thyroid issue. But, because it is a regularly undiagnosed problem, around 12 million of them don’t know it.

“Thyroids” is also a name for the hormones that the thyroid gland produces, and they are essential for metabolism, energy use, warmth, and for the proper functioning of the heart, muscles, brain, and many other organs.

These hormones are secreted by the thyroid gland into the bloodstream and are then distributed to the entire body. Almost every cell in the human body needs thyroid hormones to regulate its metabolism. This is how important these hormones are.

In development, the thyroid gland starts off in the back of the tongue when the fetus is in utero. It then begins to slowly migrate towards the front, reaching the neck before birth. There are rare cases when the migration either gets stalled, and the thyroid remains in the back of the tongue, or it goes too fast, and the thyroid ends up in the chest.

The thyroid gland produces the hormones necessary for controlling metabolism, helping to regulate such processes as heart rate, body weight, breathing, menstruation, body temperature, cholesterol, muscle strength, and more.

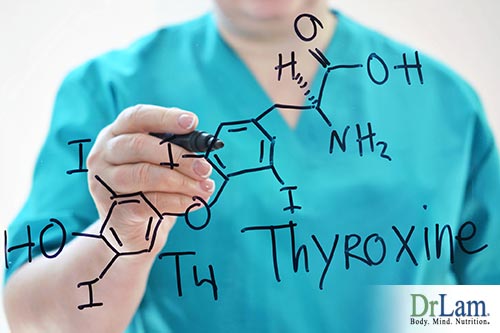

Thyrocytes are the thyroid cells that produce thyroid hormones. They create the hormones triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) by combining iodine taken from food with tyrosine, an amino acid that is used to synthesize proteins.

Thyroid cells are the only cells in the body that can absorb iodine. They make four times as much T4 as they do T3, but T3 is about four times as strong as T4. They also produce small amounts of T1 and T2 hormones, whose functions are not yet fully understood.

Thyroid cells are the only cells in the body that can absorb iodine. They make four times as much T4 as they do T3, but T3 is about four times as strong as T4. They also produce small amounts of T1 and T2 hormones, whose functions are not yet fully understood.

T3 is the active hormone, while T4 is the prohormone. The human body only has T3 receptors, so T4 is converted into the active T3.

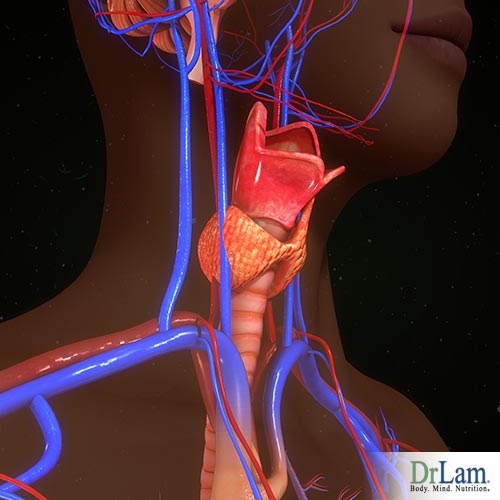

In order to produce and secrete thyroid hormones, the thyroid has to be stimulated into doing so. Then, when there is enough thyroid hormone in the bloodstream, the thyroid needs to be inhibited.

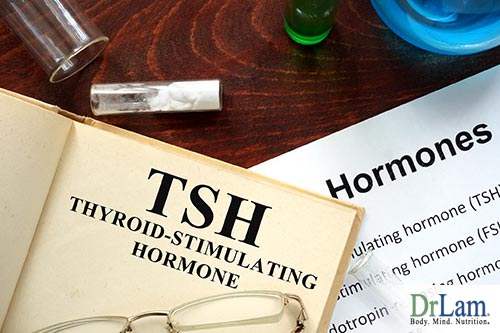

This mechanism is controlled by the hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain. First, the hypothalamus secretes the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), which tells the pituitary gland to release the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). TSH signals the thyroid gland to produce T3 and T4.

These two hormones should remain at optimal levels for the body to function properly. Too much or too little of either one and eventually signs of hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism will appear.

The delicate balance is maintained through TSH. If T3 and T4 hormones are too high, the release of TSH by the pituitary is decreased. In this case, the thyroid is not stimulated into more hormone production. If the levels are too low, then more TSH is released to stimulate the thyroid gland.

You can imagine the pituitary like a sensor that gauges when to turn on or turn off the thyroid. It is given an optimal setting by the hypothalamus, then it analyzes the blood levels of T3 and T4 accordingly and either releases or stops releasing TSH.

Like any of the body’s hormone systems, this equilibrium can get off balance. With hyperthyroidism, any number of causal factors can affect each one of the organs involved in thyroid function. Some issues that could occur include:

The thyroid hormones T3 and T4 are partially made of iodine, and their names refer to how many iodine molecules they contain. T3, or triiodothyronine, has three iodine molecules, and T4, or thyroxine, has four.

T4 is the major form of thyroid hormone found in the blood and has a longer half-life than T3, meaning it takes longer for T4 to lose half of its physiological activity. The thyroid produces 20% of the T3 the body needs, while the other 80% is obtained from the conversion of T4 to T3.

T4 is the major form of thyroid hormone found in the blood and has a longer half-life than T3, meaning it takes longer for T4 to lose half of its physiological activity. The thyroid produces 20% of the T3 the body needs, while the other 80% is obtained from the conversion of T4 to T3.

T4 is the prohormone for T3. A prohormone is the precursor of another hormone, and it is an inactive form of the hormone it is to be converted to. It doesn’t have much of an effect other than to circulate in the bloodstream until it is needed for conversion. T4 is converted to T3 by a process of deiodination, the removal of one iodine molecule within the cells by deiodinases.

Deiodinases are selenium-containing enzymes. Thyroid hormones also need iodine. Thus, a deficiency in dietary iodine or selenium can inhibit production of the T3 hormone.

The daily production of thyroid hormones is approximately 100 mcg of T4 and 30 mcg of T3 (20% from the thyroid and 80% from deiodination). T1 and T2 are produced in trace amounts through the same process.

There is also a hormone called “reverse T3” ( rT3). It also has three iodine molecules, but they are arranged in a mirror image of the active T3 hormone. Reverse T3 blocks receptor sites of T3, and it may also have actions of its own, beyond the blocking, that we’re currently unaware of. This rT3 acts as a braking mechanism, reducing the amount of T4 to T3 conversion due to shunting effect. When the body wants to slow down the metabolism, it makes less T3 and more rT3.

Thyroid hormones help with many important functions, including:

If T3 and T4 levels are too low in the system, these functions will begin to slow down. For example, heart rate and the rate at which the intestines process food may slow down. That’s why constipation and weight gain are common signs of hypothyroidism.

On the other hand, if T3 and T4 levels are too high in the system, you can have increased heart rate, diarrhea, and weight loss – all signs of hyperthyroidism.

However, the level of T3 and T4 in the blood is not the only factor in causing hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. For instance, there could be issues with T4 to T3 conversion. This means that even if the level of T4 in the blood is good, it is not turning into the needed T3. This could be caused by things like:

Worldwide, iodine deficiency and a condition called goiter are the most common triggers of signs of hypothyroidism and primary hypothyroidism, which is when the thyroid gland itself is underactive.

Worldwide, iodine deficiency and a condition called goiter are the most common triggers of signs of hypothyroidism and primary hypothyroidism, which is when the thyroid gland itself is underactive.

“Goiter” just means the thyroid gland is enlarged, but it does not mean that the gland is not working properly. This is why goiter can be present in a thyroid that is hyperactive as well.

The reason it becomes enlarged when there is iodine deficiency is because, without enough iodine, the thyroid cannot produce enough thyroid hormones. Low T3 and T4 levels in the blood cause the pituitary gland to secrete more TSH, which then stimulates the thyroid to produce hormones, making it grow in size. As it receives more TSH, the thyroid enlarges more and more. This is a goiter.

When iodine deficiency is not present, the next most common cause of hypothyroidism and goiters is the autoimmune disease Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which will be covered in more detail below.

Another cause of goiters is a condition called multinodular goiters, where the thyroid gland contains nodules. The cause of multinodular goiters is still unknown.

Other than that, goiters can be caused by injury, tumors, infections, and genetic defects. Goiters, nodules, and tumors are sometimes removed surgically. In some cases, the entire thyroid is removed. The removal of part or all of the thyroid creates hypothyroidism.

Other causes of signs of hypothyroidism include congenital hypothyroidism, certain drugs, thyroid radiation treatment, and inflammation.

With congenital hypothyroidism, a baby is born with an underdeveloped or malfunctioning thyroid. This creates problems with growth and intellectual development later on, and it needs to be addressed early in order to avoid these issues. This is why, in the US for example, newborns are tested for hypothyroidism.

Drugs, such as amiodarone, beta-blockers, and Dilantin, can also get in the way of healthy thyroid function and hormone production. Other drugs, such as lithium for bipolar disorder, and interferon alpha for cancer treatment, can also cause hypothyroidism. The inflammation these medications create will last as long as the medication is taken.

Patients with cancer in the head and neck sometimes receive radiation therapy in the affected area, which can harm the thyroid gland and cause hypothyroidism. Also, those with hyperthyroidism are sometimes treated with radioactive iodine, which then can destroy the thyroid cells to the extent of causing hypothyroidism.

Women and those over 60 years of age are more prone to hypothyroidism. A family history of hypothyroidism increases the likelihood of developing the disease. Having other diseases also increases the likelihood of getting hypothyroidism, including type 1 diabetes, Turner syndrome, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and pernicious anemia.

Inflammation of the thyroid, or thyroiditis, creates a leakage of the hormones from the gland, which actually first leads to hyperthyroidism. Eventually, it turns into hypothyroidism, which can last up to a year and a half, if not permanently.

Inflammation of the thyroid, or thyroiditis, creates a leakage of the hormones from the gland, which actually first leads to hyperthyroidism. Eventually, it turns into hypothyroidism, which can last up to a year and a half, if not permanently.

There are a few different types of thyroiditis:

Autoimmune disorders are caused by the immune system attacking the body’s cells. In this case, the immune system attacks the thyroid gland with antibodies, damaging its cells and making it less capable of hormone production.

Autoimmunity of the thyroid is the most common, organ-specific autoimmunity. It affects between 5% and 10% of the population in the US and other western countries. There are two types of autoimmune thyroid disorders: Grave’s disease, which creates hyperthyroidism, and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, which creates hypothyroidism.

Although the exact causes of autoimmune thyroid diseases are not known, genetic susceptibility combined with environmental factors appears to be the trigger of thyroid autoimmunity. These genes include thyroid-specific ones, such as the TSH receptor, thyroid peroxidase (TPO), and thyroglobulin genes. Also, immune-modulating genes, like the major histocompatibility complex, seem to play a role as well.

TPO is an enzyme that helps in the production of T3 and T4. Thyroglobulin is a protein produced in the thyroid and a precursor of thyroid hormones.

Most TSH receptor antibodies stimulate the thyroid and cause hyperthyroidism. The thyroglobulin and TPO antibodies damage thyrocytes, causing hypothyroidism.

Although at the moment it is still not well understood which, and how, environmental factors play a role in inducing thyroid autoimmunity, it is certain that TPO antibodies appear in the system before hypothyroidism and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis manifest.

Mental and emotional factors also seem to be part of the equation, as are systemic autoimmune diseases and papillary thyroid cancer.

To screen for autoimmune thyroid disorders, patients are tested for anti-thyroid antibodies. In general, TPO antibodies are positive in 90% of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and 70% of Grave’s disease.

TSH receptor antibodies are positive in 70-100% of Grave’s disease cases. Thyroglobulin antibodies are positive in 70% of Hashimoto’s and 30% of Grave’s cases.

It is interesting to note, however, that these antibodies can be present in non-thyroid autoimmune disorders as well. In about 10-15% of normal people, the TPO antibodies are high, possibly because their bodies are in a hyperactive immune state by nature. They may have symptoms of low thyroid function, but they do not have autoimmune disease. Overall, the incidence of positive TPO antibodies in sub-clinical autoimmune disorders (meaning with little or no symptoms) is very high.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is the most common cause of hypothyroidism without iodine deficiency. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is also called chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis because the lymphocytes, or lymphatic white blood cells, sent by the immune system to the thyroid, are what damage the thyrocytes.

Although it is a disease that is more likely to develop if you have a family history of it, the triggering cause of the antibodies is not yet fully understood. As these antibodies attack the thyroid gland, the gland begins gradually to lose its ability to produce enough thyroid hormones.

When T3 and T4 levels begin to dip, the pituitary will sense that and release more TSH, stimulating the thyroid and making it grow in size, also causing goiter in many cases.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is a very slow disease, and so symptoms do not usually show in the early stages. Those with Hashimoto’s will usually begin to get goiter and signs of hypothyroidism after considerable damage has already been done to the thyroid cells.

If you are experiencing any sign of hypothyroidism, you should go to the doctor to have a physical examination done to check for enlargement and a lab test to check for hormone levels and antibodies.

If you are experiencing any sign of hypothyroidism, you should go to the doctor to have a physical examination done to check for enlargement and a lab test to check for hormone levels and antibodies.

If the test is positive for TPO antibodies, that is an indication you have Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. However, if there is no goiter or hypothyroidism present, you will not need medication yet. If there is hypothyroidism, you will most likely be put on thyroid hormone replacements for the rest of your life. Most people with Hashimoto’s who take the right medication and maintain a healthy lifestyle live full, normal lives.

Some hypothyroidism is caused by not having enough TSH secretion by the pituitary gland or TRH by the hypothalamus, though it is much less common than primary hypothyroidism.

With secondary hypothyroidism, TSH is low due to the failure of pituitary control. Tertiary hypothyroidism occurs when TSH is low due to the failure of hypothalamic control. These two types fall under the umbrella term “central hypothyroidism.”

These failures occur due to disorders of the pituitary gland or hypothalamus. Pituitary adenomas, or tumors, and the surgery and radiation used to address these tumors, is the most common cause.

In primary hypothyroidism, there can be a clinical presentation where T3 and T4 are low and TSH is high, or it can have a sub-clinical presentation where T3 and T4 are normal and TSH is normal to low.

This is one of the reasons why using only TSH levels as the marker for hypothyroidism does not give very accurate results for sub-clinical primary hypothyroidism or central hypothyroidism. Medication would result in a low-to-normal TSH range, which is already a little arbitrary. You may end up thinking everything is fine, when in reality there may be a lack of T3 and T4 production.

This is why it is important to get additional tests and consider the signs of hypothyroidism that may be showing.

There are many symptoms and signs of hypothyroidism, and they usually differ from person to person. These are among the most common:

There are also many other symptoms and signs of hypothyroidism that are less common and can be categorized under different areas.

Head and neck symptoms:

Chest and heart symptoms:

Abdominal and gastrointestinal (GI) tract symptoms:

Signs of Hypothyroidism, Menstruation and reproductive symptoms:

Sleep and energy levels:

Infections and inflammation symptoms:

Mental and emotional symptoms:

Of course, many of these symptoms may not be related to the disease and in fact may be indicative of something else altogether. Because it is a slow disease, signs of hypothyroidism may not appear for months or even years after developing it. The trick is to confirm lab tests with symptoms.

Although hypothyroidism can be an underdiagnosed condition, there is also a tendency to dole out medication to anyone who complains of tiredness with lab tests showing some marginal sign of hypothyroidism, no matter the actual cause. The medications and dosages should be tailored to an individual’s needs, however, especially if there is another condition present that affects the thyroid, like adrenal fatigue.

Many of the symptoms of adrenal fatigue are similar to the signs of hypothyroidism, so it is important to make sure you get the right tests done in order to have the best plan for recovery from either (or both) conditions.

Many of the symptoms of adrenal fatigue are similar to the signs of hypothyroidism, so it is important to make sure you get the right tests done in order to have the best plan for recovery from either (or both) conditions.

The truth is, conventional lab tests done to check for hypothyroidism are not sensitive enough. A TSH test alone doesn’t take into consideration many important factors discussed above, such as adrenal weakness

Remember, TSH is the thyroid-stimulating hormone that is sent by the pituitary gland in response to the signal sent by the hypothalamus in the form of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH). It is the hormone that stimulates the thyroid to produce more T3 and T4. Looking at TSH alone means only looking at the pituitary signal, rather than directly at thyroid hormone production.

It’s a bit like looking at the luteinizing hormone (LH) sent by the pituitary to trigger ovulation in women or testosterone production in men. Wouldn’t it be more accurate to assess ovulation markers or testosterone levels directly rather than only looking at LH?

It is similar with TSH. Another important question is: what is normal TSH? It has been getting lower throughout the years. At one time it used to be 10, now it’s 2.5 - 3.2 in most endocrine journals, and some doctors report their patients feel at their best when it is under 1.5.

The fact is, there’s a continuum between euthyroid (normally functioning thyroid) and hypothyroid, just like there is a continuum between normal and elevated TSH. The distinction between normal and elevated TSH is arbitrary. In Americans, the mean TSH is 1.4. The percentage of the American population with positive TPO antibodies is around 13%.

Thankfully, there are now other tests that check for hypothyroidism, including the free T3 test and the free T4 test. Also, looking for the clinical symptoms and signs of hypothyroidism is a great way to confirm the lab test results.

With regards to free T3, the normal range is between 2.3 and 4.3 pg/mL. With reverse T3, the normal range is between 90 and 350 pg/mL, with the optimal lower quartile below 200.

Though it’s not something that most doctors will check when you show signs of hypothyroidism and complain of fatigue, adrenal function is hormonally linked with the thyroid gland. In fact, adrenal fatigue can be a causal factor in hypothyroidism, and hypothyroidism can create a stress overload for the adrenal glands.

The adrenals are two small glands that are located right above the kidneys. They are part of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is a hormone cascade. The adrenal and thyroid glands are both are linked to the hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain.

Both work by receiving hormone signals from the hypothalamus and pituitary gland that stimulate them to secrete their own hormones into the bloodstream. They are also both part of the endocrine system.

Both work by receiving hormone signals from the hypothalamus and pituitary gland that stimulate them to secrete their own hormones into the bloodstream. They are also both part of the endocrine system.

The adrenal glands produce over 50 different types of hormones, including the adrenaline needed for the “fight or flight” response, as well as cortisol, which is the body’s main anti-stress hormone. Cortisol helps regulate blood sugar, maintains heart and blood vessel function, regulates blood pressure, suppresses the immune system, and neutralizes inflammation.

The adrenals are made to deal with stress by secreting more cortisol, adrenaline, and norepinephrine. But they are not made to deal with constant stress. Many health problems arise when acute stress turns into chronic stress, and that includes the dysregulation of the adrenal glands.

What happens is that, at first, the adrenals will produce more cortisol to try and deal with the stress, as seen in the first stages of Adrenal Fatigue Syndrome (AFS). Eventually though, they become overworked, and their cortisol production drops. This is what causes the more severe symptoms in advanced AFS.

Symptoms of AFS include fatigue, weight gain, difficulty losing weight, mild depression, anxiety, heart palpitations, difficulty falling asleep, frequent colds and flus, waking up in the middle of the night, sensitivity to certain foods and drugs, PMS, fertility issues, low libido, and more.

As you can see, these symptoms are quite similar to the symptoms and signs of hypothyroidism.

Chronic stress can also create problems beyond the adrenals, which are the first line of defense. As they begin to fail, other systems follow.

The HPA axis is only part of the body’s global counter-stress mechanism, called the NeuroEndoMetabolic (NEM) Stress Response. The NEM is composed of six circuits of organs and systems all working together to navigate and deal with the harmful effects of stress. These circuits are the neuroaffect, metabolism, inflammation, cardionomic, hormone, and detoxification responses.

Like the adrenal glands, these circuits are also susceptible to dysregulation if the stress does not decrease. This can create even more inflammation and a host of other problems. Like the adrenal glands, the other organs and systems of the NEM stress response are also affected by the thyroid gland.

The NEM circuits fall into two main groups: the neuroendocrine and the metabolic response circuits. The neuroendocrine circuits include the neuroaffect, hormone, and cardionomic responses. The organs and systems involved in these circuits are the adrenals, thyroid, heart, brain, autonomic nervous system, and GI tract. They are triggered into action when the HPA axis is activated.

The metabolic circuits include the inflammation, detoxification, and metabolism circuits. They involve the liver, immune system, microbiome, pancreas, and extracellular matrix. They are triggered into action at the same time as the neuroendocrine system, as the two parts work together to mount a response to stress.

The metabolic circuits include the inflammation, detoxification, and metabolism circuits. They involve the liver, immune system, microbiome, pancreas, and extracellular matrix. They are triggered into action at the same time as the neuroendocrine system, as the two parts work together to mount a response to stress.

The thyroids are part of the hormone response circuit of the NEM, together with the adrenals and gonads (whether male or female). They form the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. The signals that control them are sent from the hypothalamus and pituitary glands in the brain, in the same manner as the HPA axis.

Within this ecosystem, the thyroid gland is responsible for the speed of the overall stress response, which means that if it is not functioning properly, stress will not be neutralized quickly enough and fatigue will ensue. With chronic tiredness, reproduction takes a back seat, and the Ovarian Adrenal Thyroid (OAT) hormonal axis becomes disrupted.

Symptoms of this disruption include fatigue, low libido, PMS, infertility, hair thinning, irregular menses, and a host of other issues. It can also lead to low thyroid function and signs of hypothyroidism, even if you are on thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Unfortunately, the more dysregulated the NEM is, the worse thyroid function gets. Low thyroid function is actually a compensatory response to the dysregulation of the NEM circuits. By bringing down thyroid function, the body slows its metabolic rate and conserves energy.

The problem is that thyroid hormone replacement therapy will not address the root cause, NEM dysregulation, leaving the underlying issues to worsen over time. The relief is temporary and symptoms eventually return.

The metabolic response also involves the thyroid, as well as the liver and pancreas. When the metabolic response is optimal, it helps the body get the exact amount of fuel it needs at the right time. When stress is encountered, this response helps increase the basal metabolic rate so that you can handle the situation at hand.

The thyroid regulates the speed of this response. Thus, when thyroid function is not optimal, this entire response is affected, and you are not able to deal with stressful situations effectively.

So what do you do if you have signs of hypothyroidism and you suspect that AFS could be involved? You should get your adrenals checked to make sure they are not a causal issue. If they are, the medications you will be given to manage your hypothyroidism will not relieve all of the symptoms, because they will not bring about full hormonal balance.

This is what many people go through when they try to heal their thyroid without knowing their adrenals are also in an unhealthy state. They try everything, including medications, and still never feel normal and healthy. They might even be taking T3 and T4 hormone replacement, and it may work for a while as it reduces the stress caused by low thyroid hormone, but it is only temporary, as the adrenal fatigue is not also addressed.

This goes even further. Hypothyroidism can trigger adrenal fatigue that was not there before. The stress and damage the lack of thyroid hormones causes the body, if left unaddressed, puts a huge load on the adrenal glands to produce cortisol, which eventually weakens them.

If it turns out that your adrenals are in a weak condition, you need to support them in order for them to support your thyroid. Your thyroid will improve when you support your adrenals.

There are two different approaches to dealing with having both hypothyroidism and AFS.

The first method is called the serial approach, where you work on one hormone at a time, helping to strengthen one organ at a time, before moving to the next. In this case, you might strengthen your adrenals through an adrenal fatigue diet and exercise program, and then deal with your thyroid issues.

The other method is the parallel approach, working on both conditions simultaneously so you can feel better as soon as possible.

The approach you take will depend on the doctor you are working with, as well as how much time and effort you are willing to dedicate to lifestyle and dietary changes.

Although almost all types of hypothyroidism are incurable, the condition can be managed using hormone replacement therapy. The prognosis is excellent and there are rarely any side effects. At the moment, the most common form of hormone for hypothyroidism is synthetic thyroid hormone replacement in the amount you need and no longer produce naturally.

This helps bring equilibrium back to your thyroid hormone levels, allowing the metabolic functions that thyroid hormones conduct.

For T4 replacement, a synthetic thyroxine pill is taken. Its dosage needs to be measured accurately because if you take too much, you will begin to exhibit signs of hyperthyroidism, while if you take too little, signs of hypothyroidism will return. All brands of this contain synthetic thyroxine and only differ in their inactive ingredients.

When you first discover you have hypothyroidism, the initial dose is calculated according to your age, weight, and state of health (including any other existing medical conditions). Then, this dose is adjusted with regular checkups and TSH level testing.

When you first discover you have hypothyroidism, the initial dose is calculated according to your age, weight, and state of health (including any other existing medical conditions). Then, this dose is adjusted with regular checkups and TSH level testing.

T4 pills are usually only taken once a day at the same time, and it is best done first thing in the morning before eating or last thing before sleep, depending on what other medications you might be taking. It is also of utmost importance that you do not change the dose or brand without first talking with your doctor, and never stop taking these pills without talking to your doctor.

By this time, you may be wondering why you would need to take T4 and not T3 since T3 is the active hormone. And you’d be right in asking this question because there are some cases where it would be beneficial to take a combination of T3 and T4.

But, first, let’s take a look at why most hypothyroidism hormone replacements focus on T4.

First of all, T4 has a longer life span in the body than that of T3. You only need to take it once a day because its effects last that long. Taking pure T3 preparations means taking pills a few times a day because, though they are very effective, they only last a few hours before you need more.

Secondly, taking T3 several times a day will not make for a smooth, even level of hormone in the body. It can cause spikes that create symptoms similar to those of hyperthyroidism and then crashes that bring out signs of hypothyroidism.

Finally, most hypothyroid patients have a normal conversion of T4 to T3, so they don’t really need the extra T3. Most people fall into this category.

However, there are times when T3 is very useful. Some things hinder the conversion of T4 to T3, like dieting, stress, adrenal fatigue, medications, and certain deficiencies (such as selenium and zinc deficiencies). In these cases, it may be useful to take a combination of T3 and T4, with strict monitoring to ensure you are getting the right dosage with the right frequency.

There are some preparations that contain both in the same pill, but they don’t provide as much sensitivity and accuracy as taking T3 and T4 separately.

A strange practice in the medical community that is becoming quite common is recommending thyroid medications to those who complain of fatigue yet don’t even have thyroid conditions. Some only show a few of the symptoms and signs of hypothyroidism.

If that is your situation, it could help to try some natural approaches, with the permission and support of your doctor.

To begin, you need to check your iodine levels. Although most people in developed countries do not have this deficiency, if you’ve been avoiding iodized salt and eating a strict diet, this may be at the root of your issue.

If that’s the case, all that’s necessary is adding iodine to your diet. Just eat more kelp, eggs, spinach, garlic, sesame seeds, and other iodine-rich foods. You can do an internet search for this and find a long list of ingredients to incorporate into daily meals.

You should also take care of your nutrition on the whole. Avoid foods and supplements that you might be sensitive to, such as gluten or dairy. Avoid consuming too much sugar and caffeine. Foods known to affect hormones, like soy, should be eaten with care. Observe how they affect you, and see if you need to avoid them as well.

The great thing is that eating a clean, healthy diet will support not only your thyroids but your adrenals as well. As mentioned before, strong adrenals will help your thyroid.

The great thing is that eating a clean, healthy diet will support not only your thyroids but your adrenals as well. As mentioned before, strong adrenals will help your thyroid.

The adrenal fatigue diet is a great way to do this in an organized, gentle, and effective way. Nutritional coaching is advisable for you if you suffer from both AFS and thyroid issues. You will benefit from the guidance early on and avoid some common mistakes people make with these conditions, such as loading up on coffee and sugar to get energy and then crashing.

You should also make sure you avoid the shotgun approach to supplementation as this could backfire. Though there are some supplements that can help adrenal fatigue and hypothyroidism, they sometimes cause adverse effects.

For example, glandulars, which are natural compounds extracted from the glands of certain animals, can provide needed thyroid cells or adrenal cells. But there are many different types and different strengths, and you might end up taking too much and getting hyperthyroidism for example.

In conclusion, do your best to support your adrenals and thyroid naturally by making lifestyle changes to reduce stress, eating a diet to optimize health and support hormones, doing the right kind of exercise for your body, and getting holistic medical guidance from a doctor who is experienced in both conditions.

You will find that gradually, your well-being will return, and you will feel energetic again once you address the root causes of your conditions. A normal, healthy life is possible after recovery.

Understanding the signs of hypothyroidism can save you years of being unwell as you begin getting the right support for your condition early on. Hypothyroidism is a very common condition, and it affects the body’s entire ecosystem. Feeling better is right around the corner if you address the root causes.