The health of the brain and nervous system is intricately tied to the health of the body, the foods you eat, the lifestyle you lead, and the environment you live in. And recently, a lot of evidence has been suggesting that neuroinflammation can be caused or worsened by unhealthy eating habits. Nutritional deficiencies are very common when eating the Standard American Diet, and in this article, we’ll focus on a very important brain nutrient: magnesium.

For a long time, people, even those in the medical community, were under the false impression that the brain was this untouchable controller of the body, separate from and superior to the older systems that keep an organism alive, such as digestion, circulation, and detoxification. But of course, the body and brain operate together as one, and we’re now seeing just how much each organ and system really affects the whole.

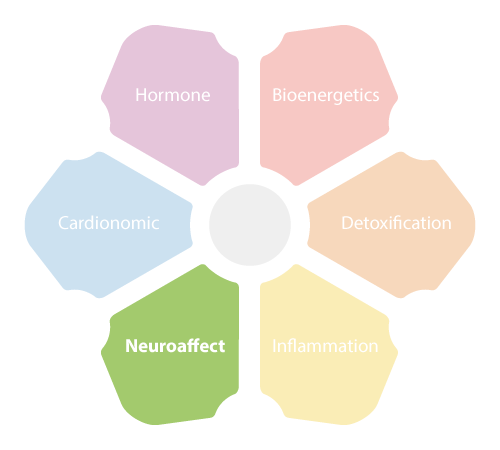

The body has a built-in mechanism that handles stress by bringing together six circuits of organs and systems that act as the body’s global stress response: the NeuroEndoMetabolic (NEM) Stress Response. The NEM’s six circuits are the Hormone, the Bioenergetics, the Cardionomic, the Neuroaffect, the Inflammation, and the Detoxification circuits. And each circuit is made up of three associated physiological components, with some overlap between circuits.

The body has a built-in mechanism that handles stress by bringing together six circuits of organs and systems that act as the body’s global stress response: the NeuroEndoMetabolic (NEM) Stress Response. The NEM’s six circuits are the Hormone, the Bioenergetics, the Cardionomic, the Neuroaffect, the Inflammation, and the Detoxification circuits. And each circuit is made up of three associated physiological components, with some overlap between circuits.

Because we will be describing the health benefits of magnesium on the brain and nervous system in this article, we’ll be talking a lot about the Neuroaffect circuit, which is composed of the brain, the autonomic nervous system (ANS), and the microbiome. The microbiome in this circuit refers mainly to the gut microbiome - the ecosystem of microbes that live in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Though it would have come as a surprise a few decades ago to include the microbiome in this triad, it shouldn’t be surprising anymore. The link between the gut and the brain is undeniable, and in fact, one of the branches of the nervous system is the enteric nervous system, completely dedicated to innervating and sending information to and from the GI tract and the brain. In fact, in many ancient traditions, the gut was referred to as “the second brain” precisely because of its large influence on the nervous system, mood, and mental health.

If you’ve been remotely following the recent health and medical news and trends lately, you undoubtedly heard how rampant magnesium deficiency is, and how much it is negatively affecting people’s health. By some estimates, at least half the population in the US is deficient in this very important mineral, meaning the daily intake is much lower than what is required for the body to function optimally.

And because magnesium is a catalyst in over 300 enzymatic reactions, this means that all bodily functions that utilize these pathways will be affected. They include things like protein synthesis, RNA and DNA synthesis, cell signaling, energy production, energy storage, nerve function, cell growth, muscle contraction, muscle relaxation, and bone strength. Magnesium also protects the brain, as we’ll see in more detail later.

Magnesium is not the easiest nutrient to measure in the body, and though there are a variety of tests, some less accurate than others, the best option is to look at the test results against a backdrop of deficiency symptoms in order to identify what is going on in your body. Symptoms of magnesium deficiency include:

Conditions that are aggravated by this deficiency include:

From a bird’s eye view, you can think of magnesium as the nutrient that relaxes the body and mind, and its lack creates tension and tightness in the body and mind. It has been shown to have anti-anxiety properties, antidepressant properties, and muscle-relaxant properties.

All of the above symptoms and conditions are huge stressors on the body, and so if they are not addressed, they will eventually lead to adrenal fatigue and the dysregulation of the NEM stress response, which bring along with them their own set of symptoms and health conditions. In that sense, addressing magnesium deficiency as early as possible can help stave off these health challenges.

Stress permeates much of modern life; it’s baked into the way we work, the way we interact, and even into our holidays. And although your body is equipped to handle stress, and your NEM is a very sophisticated stress response that has many adaptive strategies, your body is not made to handle chronic stress. Chronic stress has to be one of the biggest health risks of the last few decades, and it does not show any signs of improvement.

Chronic stress, whether physical, such as from an unhealthy diet or a chronic condition, or psychological, such as mental health issues or problems at work or at home, overworks the adrenal glands, which are part of the NEM’s Hormone circuit. The adrenal glands are the body’s first line of defense, and they are activated as part of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

Chronic stress, whether physical, such as from an unhealthy diet or a chronic condition, or psychological, such as mental health issues or problems at work or at home, overworks the adrenal glands, which are part of the NEM’s Hormone circuit. The adrenal glands are the body’s first line of defense, and they are activated as part of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

The hypothalamus and pituitary gland in the brain act as the control center, where the hypothalamus receives information that a stressor is present and signals to the pituitary gland to release ACTH, which then stimulates the adrenal glands sitting atop the kidneys to produce cortisol, the body’s main anti-stress hormone.

Cortisol has many important functions, such as regulating blood glucose and blood pressure levels, maintaining heart and blood vessel function, suppressing the immune system and neutralizing inflammation. It is one of over 50 hormones produced by the adrenal glands.

Although one of cortisol’s roles is to neutralize inflammation, when its levels increase in the system, it can actually create more inflammation. And in the beginning stages of Adrenal Fatigue Syndrome (AFS), that’s exactly what happens.

AFS is the condition that results when stress becomes chronic and the adrenals are overworking. At first, they produce more and more cortisol to meet the growing demand, but once they are exhausted, their cortisol output drops and the rest of the NEM has to compensate for that loss.

Symptoms of AFS include fatigue, insomnia, weight gain, brain fog, PMS, infertility, low libido, hair loss, lowered immunity, food and drug sensitivities, an inability to handle stress, heart palpitations, mild depression, anxiety, and digestive issues.

Cortisol has a direct effect on the brain and nervous system, as well as on mental health. For one, the hippocampus, which is the area of the brain that consolidates memories, has more cortisol receptors than any other part of the brain. And this can even be seen on MRIs, where if you look at the image of the brain of someone with chronic stress, the hippocampus is lit up with activity, due to all the cortisol receptors firing up.

What happens in these cases, if the stress is left unaddressed and cortisol keeps flooding the hippocampus, is that the hippocampus will shrink. You can see in images of the brains of people with severe psychological trauma or PTSD that their hippocampi are smaller than average.

But the rest of the brain is also affected by cortisol, as there are cortisol receptors in the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and the locus coeruleus. All of these areas, along with the hippocampus, can become vulnerable to inflammation, which is another risk with chronic stress and AFS.

Inflammation is a natural and healthy part of the immune response, it’s responsible for getting rid of the original insult, whether that’s a pathogen or toxin, as well as the dead and damaged cells left behind. Mild inflammation is even beneficial for the brain and nervous system; it’s part of their defense system.

But just like stress, when inflammation becomes chronic, it causes a lot of damage. And one of the key components of neuroinflammation is the activation of microglial cells. The microglia are a type of glial cell that accounts for around 10-15% of the cells in the brain, and they are also found in the spinal cord. Their job is to act as the main immune defense in the central nervous system (CNS), and they do so by surveilling the CNS for any damaged or dead neurons, damaged synapses, pathogens, toxins, plaques, or any other harmful substance. You can think of them as the innate immune cells of your CNS.

These microglia are activated in response to neural injury or acute inflammation of the brain. They act very quickly, and they also generate reactive oxygen species, or free radicals, when they are activated. When the microglia are switched on, due to whatever trigger, they begin to upregulate, becoming more and more active, and as that happens, they also begin to release neurotoxic compounds.

These neurotoxic compounds can damage local dendrites, which are the branches of the neuron that pass on signals from one neuron to the next. When these dendrites are damaged and start to die off, the microglia sense this and upregulate even more. And chronic microglial activation causes a constant release of inflammatory mediators, and the blood-brain barrier becomes more permeable to circulating blood components and peripheral immune cells, like T cells, B cells, and macrophages.

A permeable blood-brain barrier is quite dangerous, as it allows important compounds to leak out from the brain while letting possibly harmful substances into the brain.

This cycle of chronic microglial activation creates systemic inflammation in the CNS, and that can lead to neuronal dysfunction, neuronal injury, neuronal death, chronic neurodegenerative conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, and neurobehavioral impairment.

Microglial cell activation also plays a role in:

So, what triggers microglial cell activation and neuroinflammation in the first place? There are several factors that can do that:

People who are exposed to more than one of these triggers will be more vulnerable to neuroinflammation and chronic microglial cell activation than those exposed to just one.

The three components of the Neuroaffect circuit: the brain, microbiome, and ANS. These are involved when inflammation begins to spread throughout the body, particularly the type of inflammation that begins in the gut and spreads to the nervous system. And actually, most inflammation begins in the gut, and for good reason.

The three components of the Neuroaffect circuit: the brain, microbiome, and ANS. These are involved when inflammation begins to spread throughout the body, particularly the type of inflammation that begins in the gut and spreads to the nervous system. And actually, most inflammation begins in the gut, and for good reason.

Your gut contains two-thirds of your immune cells in what is called the gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT). That’s why the Inflammation circuit of the NEM is composed of the immune system, gut, and microbiome. When you ingest certain things, like toxins, pathogens, or even foods that you are sensitive to, your immune system will attack them in order to prevent them from spreading via your bloodstream to the rest of your body.

Thankfully, your gut lining is made up of cells that form tight junctions with each other in order to only let in nutrients from the food you’ve digested. But there are certain factors that increase the risk that these junctions will begin to loosen up and allow substances to cross from your gut into your bloodstream that really shouldn’t be there.

This often happens when your microbiome is not in balance – a state called dysbiosis – where the “bad” bacteria begin to outnumber the “good” bacteria in your gut. Dysbiosis is caused by things like eating an unhealthy diet, overconsumption of sugar, overconsumption of alcohol, taking antibiotics, taking NSAIDs or opioids, ingesting toxins or chemicals, and chronic stress.

Remember, chronic stress causes your adrenal glands to secrete more cortisol, which can increase inflammation in the body, especially in the gut.

Dysbiosis leads to a leaky gut, and a leaky gut will allow substances into the bloodstream that will prompt an immune system attack. With immune activation comes inflammation, and since these leaks and the dysbiosis that caused them have not been addressed, the immune system keeps getting triggered and chronic inflammation ensues.

Persistent inflammation in the gut will eventually spread to other parts of the body, such as to the joints, skin or nervous system, creating symptoms there that you wouldn’t normally attribute to an issue with the GI tract. A common example of this is gluten. Gluten affects both the GI tract and the brain, and some people have a gluten sensitivity that does not manifest digestive issues, yet they will experience brain fog and other neurological problems.

When there is dysbiosis, the gut produces cytokines, and these cytokines have been found to influence sleep. Sleep disruptions, in turn, increase the presence of these pro-inflammatory cytokines, creating even more inflammation and disrupting sleep even more.

All of these factors put together – the issues with sleep, inflammation, dysbiosis in the gut, and the connection between the gut and the nervous system – will have a significant effect on neurotransmitters. Firstly, because many neurotransmitters are produced or stored in the GI tract. Secondly, your body’s biological clock has a two-way relationship with neurotransmitters, with sleep being a major regulator of these neurotransmitters, and imbalances in these neurotransmitters leading to sleep dysregulation.

As you can see, the body’s different systems are interlinked, and each one affects the other in some way. This is important when trying to identify the problem so that instead of just managing symptoms, you can address the causal root. It’s also important because knowing this, you realize that improving one area of your health will help improve other areas. And one way to begin addressing many of these issues is to check for magnesium deficiency and up your intake of it.

Different animal studies have shown that a deficiency in magnesium can actually trigger an inflammatory response, with macrophages and leukocytes activated, and pro-inflammatory cytokines released. This then leads to the production of a lot of free radicals, which can lead to more inflammation and oxidative damage.

Different animal studies have shown that a deficiency in magnesium can actually trigger an inflammatory response, with macrophages and leukocytes activated, and pro-inflammatory cytokines released. This then leads to the production of a lot of free radicals, which can lead to more inflammation and oxidative damage.

Magnesium deficiency has also been associated with the low-grade inflammation that can accompany other chronic conditions. When there is sufficient intake of magnesium, this added aggravation is no longer present.

The findings of these studies give enough evidence to confirm the theory that magnesium deficiency is a significant risk factor in chronic conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. It’s also a risk factor in chronic neuroinflammation and the many health issues that it brings along with it.

Most people are not getting enough magnesium from their diet. This is due to the fact that most people are not eating a healthy, whole-foods diet that has a lot of nutrients, and also due to the fact that the soil has been depleted, and so produce doesn’t contain the amount of nutrients that it used to.

Not only are we consuming too few fresh, whole foods, and too many processed and highly refined foods, but even the fresh whole foods we do consume don’t have the amount of magnesium we actually need. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of magnesium is 300-400 mg per day, and we’re only getting around 175-260 mg per day on average from food.

But let’s say you’re eating a healthy, mainly whole-foods diet and somehow getting the RDA of magnesium; you still may not be absorbing all of it. Malabsorption is a huge problem for many people, most of whom don’t even know they suffer from it. It’s when your ability to absorb the nutrients from the food you’ve digested is reduced.

This is quite a common theme with AFS and the dysregulation of the NEM stress response. It’s also common in people that drink a lot of soft drinks, which contain phosphoric acid that then combines with magnesium to create magnesium phosphate. Magnesium phosphate is insoluble and can’t be absorbed by the small intestine, so it gets eliminated from the body. Also, a diet that is much higher in calcium than magnesium will suppress absorption.

Magnesium is one of the great relaxers of the body and mind. It has a calming effect and can help you feel less constricted and anxious. It’s also calming for the GI tract, which can improve constipation.

Magnesium is one of the great relaxers of the body and mind. It has a calming effect and can help you feel less constricted and anxious. It’s also calming for the GI tract, which can improve constipation.

For the brain and nervous system, magnesium is great for speeding up recovery from concussions. In fact, it helps prevent brain injury and post-concussion syndrome after a concussion. Interestingly enough, it’s been noted that after a concussion, the levels of magnesium in the brain drop by 50% and remain low for around five days before slowly climbing back up to pre-concussion levels. This can be remedied by upping the intake of magnesium through whole foods or supplements.

Magnesium helps reduce inflammation, including in the brain and nervous system, and it raises glutathione in cells. Glutathione is sometimes referred to as the “mother of all antioxidants” as it is one of your body’s greatest free-radical fighters. It also recycles other antioxidants, such as vitamin C, so they can keep fighting oxidative stress over and over again.

Unfortunately, although there are several tests that assess the level of magnesium in the body, none of them can be considered satisfactory. The difficulty in assessing its levels is mainly due to the fact that magnesium resides inside the cells and bones, and so checking its levels in the blood, for example, doesn’t give an accurate assessment by any means.

But just for your information, here are some of the magnesium tests available:

Since most health professionals will use the least accurate test, it’s good sense to ask in advance for a more accurate test, such as the red blood cell test or the intracellular magnesium test. The test results should also be looked at together with symptoms of deficiency you may have in order to properly identify your issue.

To resolve magnesium deficiency, the best option is to try to get as much of your magnesium through food as possible. It’s much more bioavailable, and it comes in the package of whole foods, such as plants, that help support all the systems and pathways of your body rather than just targeting one specific area. Some of the richest sources of magnesium are:

In cases where a therapeutic dose is needed, though, such as after a concussion or with severe neuroinflammation, magnesium supplements can give that necessary boost.

If you have a magnesium deficiency and you’re not able to get enough through food, for whatever reason, you will need to look at other options. Aside from working on any digestive issues you have, such as malabsorption or eating an unhealthy diet, you can also consider taking a supplement. But choosing a supplement that is right for your individual condition and needs is very important.

Now, if you have AFS, especially in the more advanced stages, you need to be very careful with supplements because your system has slowed down so much that it may not be able to process supplement ingredients properly, and that can add to the toxic load of your body or cause a paradoxical reaction, which then adds more stress on your adrenals and NEM.

With magnesium specifically, it usually causes diarrhea, and while for most people that’s not the most pleasant side effect, for those with AFS it may be a welcomed one - most people with AFS experience constipation. But, for the few that have borderline diarrhea, due to having IBS or some other digestive issue along with AFS, it can make the situation worse. Paradoxical reactions to magnesium are also quite common with AFS, and they can include things like constipation, irritation, increased fatigue, and anxiety.

Specific forms of magnesium can help with specific issues. For example, magnesium malate is good for chronic pain since it helps to reduce lactic acid build-up, magnesium glycinate is good for people needing to detox heavy metals from their system, and magnesium taurate is good for the heart.

And that’s the thing, there are many forms of magnesium supplements out there such as Mag Three, and depending on the ligand it comes with, such as oxide, lactic acid, glutamic acid, malic acid, citric acid, glycine, and orotic acid. Each one is good for a specific condition, like the examples above. But the sad fact is that the least absorbable of these, magnesium oxide, is the most commonly recommended supplement.

But thankfully, all forms of magnesium will be useful for you if you have a deficiency; it’s just that some will be more or less useful for you depending on your specific situation.

But thankfully, all forms of magnesium will be useful for you if you have a deficiency; it’s just that some will be more or less useful for you depending on your specific situation.

While selecting the right type of supplement can be a little complicated, it can make a world of difference in your health, so the best thing you can do is follow the guidance of an experienced health professional who knows how to address your health holistically and who has a deep understanding of AFS and the NEM stress response, especially the Neuroaffect circuit, when dealing with neuroinflammation.

© Copyright 2020 Michael Lam, M.D. All Rights Reserved.

Magnesium is involved in ATP production, glucose metabolism, physical and mental relaxation, heart health, and neurocognitive functions. That’s why a magnesium deficiency can be so dangerous. Learn how to prevent or remedy this risky situation, especially if you want to protect your brain health.