There’s a big difference between conventional medicine and functional medicine, and it has to do with how you look at the health of a patient. Do you try to decipher which organ or system is creating symptoms, or do you look at the entire patient’s body, mind, and environment for clues? The second approach, what we like to call the whole-person approach, looks at how all the different components interact, and how to restore balance to that interaction, and one of the most important aspects of this balance has to do with HPA axis markers.

The HPA axis, which is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, is part of the Hormone circuit of the NeuroEndoMetabolic (NEM) Stress Response. The NEM is your body’s global response to stress, and it’s made up of six circuits of organs and systems that work together when a stressor is present and then go back to a state of rest and repair when the stressor is gone. The other five circuits of the NEM are the Bioenergetics, the Cardionomic, the Neuroaffect, the Inflammation, and the Detoxification circuits.

The HPA axis, which is the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, is part of the Hormone circuit of the NeuroEndoMetabolic (NEM) Stress Response. The NEM is your body’s global response to stress, and it’s made up of six circuits of organs and systems that work together when a stressor is present and then go back to a state of rest and repair when the stressor is gone. The other five circuits of the NEM are the Bioenergetics, the Cardionomic, the Neuroaffect, the Inflammation, and the Detoxification circuits.

The Hormone circuit produces hormones that help the body fight stress and so it is part of the endocrine system, which is made up of eight glands that are found in different places throughout the body, such as the thyroid gland at the base of the throat, the adrenal glands on top of the kidneys, the ovaries to each side of the womb in women, and the testes in men.

As you can see from the name, the HPA controls the adrenal glands, which produce over 50 different hormones, with the most important anti-stress hormone being cortisol. Cortisol is in charge of important functions like regulating blood sugar and blood pressure levels, maintaining heart and blood vessel functions, suppressing the immune system once it has done its job, and neutralizing inflammation.

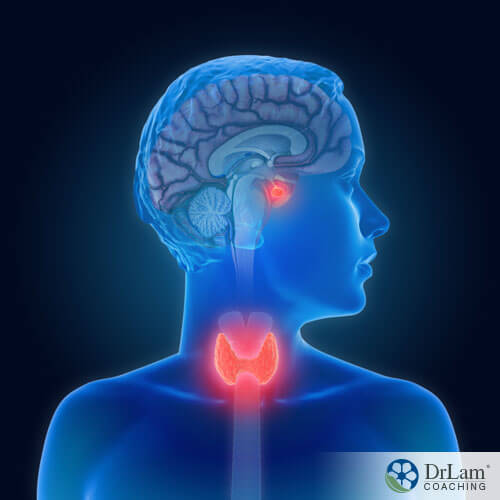

This control begins with the hypothalamus in the brain. When the hypothalamus is alerted to the presence of stress in the body, it releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH signals to the pituitary gland, also in the brain, to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which then stimulates the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol. Once the stressor has been dealt with, excess cortisol is then turned back on the pituitary gland and hypothalamus in a negative feedback loop in order to suppress their production of CRH and ACTH, thereby halting the cycle.

As for the reproductive hormones, they are controlled by the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. The ovaries are also part of the Ovarian Adrenal Thyroid (OAT) axis. Each component of the Hormone circuit and every gland of the endocrine system will be affected by the hormones released by the other components and glands, and each gland and organ of each axis is tied into other systems hormonally through other networks and axes.

That’s why if just one tiny part of this network goes off balance, the others will try to compensate, and if this imbalance isn’t corrected in time, it will throw off the entire endocrine system as well as the entire NEM.

The main anti-stress hormone that the adrenal glands produce is cortisol, although they also produce many other anti-stress hormones. Cortisol is one of the most important HPA axis markers.

The main anti-stress hormone that the adrenal glands produce is cortisol, although they also produce many other anti-stress hormones. Cortisol is one of the most important HPA axis markers.

And HPA axis markers can be measured in order to see whether they are in the normal, healthy range or if they’re out of balance. Just knowing this one piece of information can help you understand many health problems as well as what needs to be done in order to restore that balance.

Your body evolved to handle acute stress, but it cannot tell the difference between the stress of having to fight off a predator and the stress of a difficult situation at work. Either way, whenever a stressor is present, your HPA axis kicks into gear and your adrenals secrete cortisol, as well as other hormones, to help you deal with the stress. Once the stress has been dealt with, the HPA axis turns off, and your body is allowed to go back to a calmer state.

But in these modern times, a new epidemic is taking over our lives, and we have gone from experiencing acute stress once in a while to living with chronic stress on a daily basis. Chronic stress is not something your body was built for, and its effects are far-reaching. But the most immediate effects have to do with the dysregulation of HPA axis markers.

When the HPA axis is constantly switched on, it’s constantly stimulating the adrenal glands to secrete more and more cortisol, since the stress just won’t go away. This overworks the adrenals and creates an unnatural and unhealthy increase in cortisol levels in the body, which marks the beginning stages of Adrenal Fatigue Syndrome (AFS).

After a while, when the adrenals have become exhausted from overworking, they cannot produce cortisol anymore. This creates unnaturally and unhealthily low levels of cortisol in the body, which marks the more advanced stages of AFS.

Each stage brings with it a collection of symptoms as well as varying degrees of severity. The most common symptoms of AFS include fatigue, weight gain, insomnia, hair loss, brain fog, loss of libido, PMS, infertility, an inability to handle stress, anxiety, mild depression, hypoglycemia, frequent colds and flus, increased sensitivities to foods and medications, sugar and salt cravings, and heart palpitations, among many others.

When you look at that list of symptoms, at first it might seem confusing since the symptoms are so different from each other. But when you remember that the adrenal glands are part of the Hormone circuit of the NEM, where each hormone-producing gland affects all the others, you can see how connected they really are.

For example, the fatigue and lack of energy make sense when you realize that when the adrenal glands are weakened, the thyroid is as well, and the thyroid controls basal metabolic rate and the way energy is distributed in the body. When you remember that the reproductive organs are part of the circuit, you see how a loss in libido, infertility, and bad PMS can come about.

You’re probably familiar with the term “fight or flight”, which is the body’s way of preparing to deal with a threat – either by fighting it off or escaping it. This response is activated when the threat is perceived to be an imminent danger, and it readies the heart, lungs, and blood vessels to pump freshly oxygenated blood throughout the muscles so that they get more energy for that fight or flight. It also increases glucose in the blood for the same purpose.

You’re probably familiar with the term “fight or flight”, which is the body’s way of preparing to deal with a threat – either by fighting it off or escaping it. This response is activated when the threat is perceived to be an imminent danger, and it readies the heart, lungs, and blood vessels to pump freshly oxygenated blood throughout the muscles so that they get more energy for that fight or flight. It also increases glucose in the blood for the same purpose.

To trigger this response, the two key hormones (which are also neurotransmitters) needed are adrenaline and norepinephrine, which are our other two important HPA axis markers.

Adrenaline, which is sometimes called epinephrine, is an extremely powerful stimulant. It is released by the adrenal glands (as well as certain neurons), which is why they have such similar names, but it is regulated by the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The SNS is part of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), the part of the nervous system that you can’t consciously control.

Because adrenaline is so powerful, only a small and short-lived release of it is needed, and any excess of it can create health consequences, such as heart palpitations, high blood pressure, breathlessness, shortness of breath, anxiety, cardiac arrhythmia, dizziness, and atrial fibrillation. If this keeps going, damage to the heart is next.

Norepinephrine, the biochemical mother of adrenaline, it is another important hormone and neurotransmitter that helps the fight or flight response kick in. It is made in the brain where it behaves both as a neurotransmitter and a hormone. As a neurotransmitter localized in the brain, norepinephrine helps keep the brain alert, which is an important function when you need to fight off or escape a threat. As a hormone, it travels to the heart and leads to heart pounding and throbbing. The sensation of a heart “jumping out” is associated with this hormone. Overall, norepinephrine is weaker in its action than to adrenaline.

Within the central nervous system (CNS), excess norepinephrine can cause anxiety, insomnia and panic attacks. This is why when you have adrenal fatigue, and your adrenal hormones are all out of balance, you can get neurological and psychological symptoms, since these hormones can directly influence your brain and nervous system.

Although adrenaline works more on the Cardionomic circuit of the NEM and norepinephrine works more on the Neuroaffect circuit of the NEM, because, like cortisol, they are adrenal hormones and our main HPA axis markers, we consider them as also part of the Hormone circuit. And hormones are linked with the body’s biological rhythms.

The adrenal glands are told what to do by the control center in the brain, consisting of the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland. Inside your hypothalamus, above where the optic nerve crosses, there is an area called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), and this SCN is responsible for the regulation of your circadian rhythm. The SCN also communicates with other neurons in the hypothalamus to tell them to start the activation of the HPA axis.

The rest of your body’s cells, outside of the SCN, have their own clock genes as well, which are responsible for regulating the clock system in the body, or your biological clock - an umbrella term for all the different natural rhythms that certain bodily functions follow, including body temperature, sleep, alertness, and endocrine activity. These rhythms are rhythms because they follow a certain cycle, repeating again once a cycle is completed.

The SCN communicates bidirectionally with these clocks too, especially the circadian clocks in the periphery, in order to orchestrate the body’s rhythms and cycles for optimal health. The circadian rhythm helps control the 24-hour cycles in the biological clock, such as the sleep-wake cycle.

HPA axis markers are regulated by the circadian rhythm, which is regulated by the SCN according to light and darkness. So these HPA axis markers naturally rise and fall according to the time of day. During the night, when you’re supposed to be asleep, cortisol, adrenaline, and norepinephrine should be low. That’s because there’s no need to fight, flee. or have much stimulation when you’re sleeping.

About an hour after waking, cortisol should rise to its highest levels, helping you jump-start your day, and then it’s supposed to come down. This helps reset your immune system for the next 24 hours. Adrenaline and norepinephrine levels also rise during the day, and all three HPA axis markers need to come down again before sleep, so your body can enter the rest and digestion stage.

The circadian clock has a negative feedback mechanism built in, similar to that of the HPA axis. When you’re faced with acute stress and a shot of cortisol is released from the adrenals, this cortisol inhibits the feedback mechanism for a short time, but then once the stress has passed, equilibrium is reinstated in the circadian rhythm once more. With chronic stress, though, there is a constant disruption of this mechanism, and the body doesn’t get a chance to reinstate equilibrium.

When this happens, it’s very common to find the SCN, the nervous system, and the peripheral circadian clocks falling out of sync with one another.

Measuring cortisol levels in saliva, blood, or urine can help determine what the circadian rhythm is doing. For example, your first-morning urine cortisol levels can tell you what was going on at night. Taking another sample after an hour can tell you if your cortisol levels are rising as they should be. Adrenaline and norepinephrine can also be tested to see how they’ve been behaving. And all three measurements can show an overall picture of your HPA axis markers.

As we’ve seen, stress keeps the HPA axis switched on and overworks the adrenals, at first making them produce too much cortisol, and then, when they’re exhausted, too little. It’s pretty much the same thing with adrenaline and norepinephrine. And when these HPA axis markers go out of whack, you get a lot of health issues, sometimes with symptoms that don’t make sense at first.

But what kind of stressors are we talking about when we’re dealing with chronic stress? There can be many different types, and they can be physical, psychological, or environmental.

For example, certain factors can affect your biological clock and disrupt your circadian rhythm. Those include:

Physical stressors that can cause adrenal fatigue and dysregulation in HPA axis markers include:

Psychological stressors can also play a part, though they may not have as severe of an impact as physical stressors, they can make the body more susceptible to physical stressors. And they can range from being in an unhealthy relationship, to overworking, to having untreated or undiagnosed mental illness.

When testing for cortisol, adrenaline, and norepinephrine levels, all the above possibilities must be taken into account as well, because all of them can distort the natural and healthy curve that someone with normal levels would have.

For example, in some patients with breast cancer, you may find their cortisol levels don’t rise at all after waking, and their cortisol curve is flat throughout the day. But at the same time, their adrenaline and norepinephrine are off the charts, meaning they’re constantly in fight or flight mode, even at night when they should be asleep. This may be why they can experience panic attacks, anxiety, brain fog, depression, constipation, and a slew of other symptoms alongside the breast cancer itself. And, because the cortisol isn’t rising as it should be, it’s not resetting the immune system, which is needed in order to fight the cancer cells.

That makes for a very challenging situation, and you’d have to look at all the possible stressors that may be putting pressure on the adrenals, and begin to address them one by one in order to get those cortisol levels back up. For example, if a patient is taking a glucocorticoid, which is highly anti-inflammatory and pharmacologically effective, it could be causing secondary adrenal insufficiency and inhibiting the immune system indirectly. This is why you need an experienced provider who understands all the nuances of the HPA axis markers in order to provide the most accurate and best care for someone with stress-induced symptoms instead of structural causes of symptoms.

When the adrenal glands begin to break down, most people don’t understand the signs and symptoms well enough to know what’s going on. They may start to increase coffee intake, work out harder, or just push on. Even if they do go see their doctor, not many conventional medical practitioners understand or accept adrenal fatigue, and so they may misdiagnose them with another problem, such as depression or chronic fatigue syndrome. As AFS progresses without being addressed, other components of the NEM’s Hormone circuit and the endocrine system will also begin to break down, and the more the HPA axis markers will go out of balance. The next in line after the adrenal glands are usually the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas. This is where you start to see signs of derangement in glucose metabolism, and it can cause things like hypoglycemia, sugar cravings, and more fatigue.

When the adrenal glands begin to break down, most people don’t understand the signs and symptoms well enough to know what’s going on. They may start to increase coffee intake, work out harder, or just push on. Even if they do go see their doctor, not many conventional medical practitioners understand or accept adrenal fatigue, and so they may misdiagnose them with another problem, such as depression or chronic fatigue syndrome. As AFS progresses without being addressed, other components of the NEM’s Hormone circuit and the endocrine system will also begin to break down, and the more the HPA axis markers will go out of balance. The next in line after the adrenal glands are usually the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas. This is where you start to see signs of derangement in glucose metabolism, and it can cause things like hypoglycemia, sugar cravings, and more fatigue.

If you give in to these cravings, you will end up riding the roller coaster of blood sugar spikes and crashes, where when you eat a sugary food, your blood sugar levels soar, prompting the pancreas to secrete a lot of insulin, which brings your blood sugar levels crashing, prompting more sugar cravings to make up for it. This cycle is extremely detrimental for health, and it stresses the adrenal glands even more.

At this point, you may be running on the fuel of coffee, energy drinks, and sweets all day long just to get through the day, and the negative effects of this on your microbiome, your gut, your mitochondria, and your hormones are quite significant. If this keeps going, your thyroid is next in line.

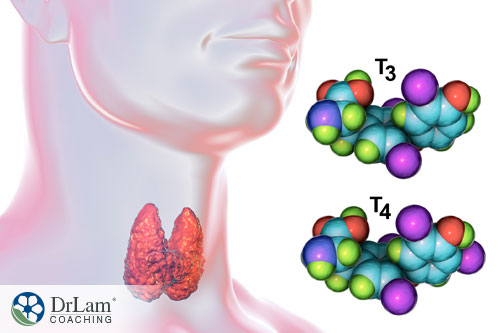

The thyroid is what helps your cells convert calories and oxygen into energy, it is responsible for regulating your body temperature, metabolism, blood pressure, heart rate, and growth. If it slows down, the entire body’s metabolism also slows down, and you may end up with chronic hypothyroidism, and if it becomes hyperactive, your body’s metabolism speeds up, and you may end up with chronic hyperthyroidism. Thyroid problems are very common, and over 10 million Americans have been diagnosed with some kind of thyroid disorder.

Stress and adrenal fatigue usually bring on more hypothyroidism than hyperthyroidism, where the thyroid is not able to produce enough of the very important thyroid hormones T3 and T4. Hypothyroidism brought on by a malfunction in another organ is called secondary hypothyroidism.

Primary hypothyroidism is a result of direct damage to the thyroid gland, such as from an autoimmune reaction, as is what happens with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Also, exposure to radiation, overconsumption of soy products, taking medications that are harmful to the thyroid (such as lithium), and the overconsumption of goitrogenic foods (such as radishes, cauliflower, broccoli, turnips, and Brussels sprouts) can lead to a sluggish thyroid.

Primary hypothyroidism is a result of direct damage to the thyroid gland, such as from an autoimmune reaction, as is what happens with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Also, exposure to radiation, overconsumption of soy products, taking medications that are harmful to the thyroid (such as lithium), and the overconsumption of goitrogenic foods (such as radishes, cauliflower, broccoli, turnips, and Brussels sprouts) can lead to a sluggish thyroid.

Symptoms of hypothyroidism include fatigue, lack of energy, dry skin, hair loss, sensitivity to cold, brain fog, depression, constipation, weight gain, high cholesterol, low libido, PMS, infertility, miscarriage, abdominal cramping, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Management of primary hypothyroidism is usually through thyroid replacement therapy, while for secondary hypothyroidism, management has to include correcting whatever organ or system malfunction brought along hypothyroidism with it, such as AFS.

In the early stages of AFS, cortisol levels are higher than normal, and although that’s needed in order to cope with stress, it also has negative health effects, and as we’ve seen, it also dysregulates other axes and systems that are linked to the adrenals.

With the OAT axis, cortisol can begin blocking progesterone receptors, making progesterone less effective in the body of a woman. Also, because some progesterone is made by the adrenals, and the adrenals are now fully dedicated to cortisol production, the production of cortisol is favored over progesterone production, and so progesterone production begins to decline.

Reduced progesterone can lead to the relative dominance of estrogen in the system. It’s not about how much progesterone or estrogen is in the system so much as it is about the balance between the two. Progesterone acts as an antagonist to estrogen, and so when there is a relative dominance of estrogen to progesterone, we call that state estrogen dominance, and it brings about its own set of health problems.

Conditions associated with estrogen dominance include PMS, fibroids, pre-menopausal syndrome, infertility, weight gain, the proliferation of the endometrium, fibrocystic breast disease, breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and loss of bone mass.

Estrogen dominance can also develop in the absence of adrenal fatigue and the dysregulation of HPA axis markers. It can result from a poor diet, overexposure to environmental estrogens, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and from taking unopposed estrogen in hormone replacement therapy.

High levels of estrogen interfere with the release of cortisol from the adrenals, and they also increase the amount of cortisol-binding and thyroid-binding proteins in the blood. This means that it’s possible for you to get blood tests on your thyroid hormones and cortisol levels, only to be in the normal ranges, but on a sub-clinical level, you may still have insufficient amounts of thyroid hormones in your tissues or free cortisol that is available for use.

In that sense, estrogen dominance can lead to adrenal fatigue and hypothyroidism, and if those develop, they will worsen estrogen dominance, which will worsen these conditions even more.

Although this may become quite confusing when considering care options, in most cases, dealing with adrenal fatigue and HPA axis dysregulation first seems to lighten the burden on the HPG and OAT axes.

No matter how much hormone replacement you take, if your adrenals are weak, you will not clear up estrogen or thyroid issues completely. But, if these issues were caused by adrenal fatigue, which is a common occurrence, then you may not need hormone replacement at all. What you actually may need is to strengthen the adrenals and bring back harmony to the SCN, the HPA axis markers, and the peripheral biological clocks.

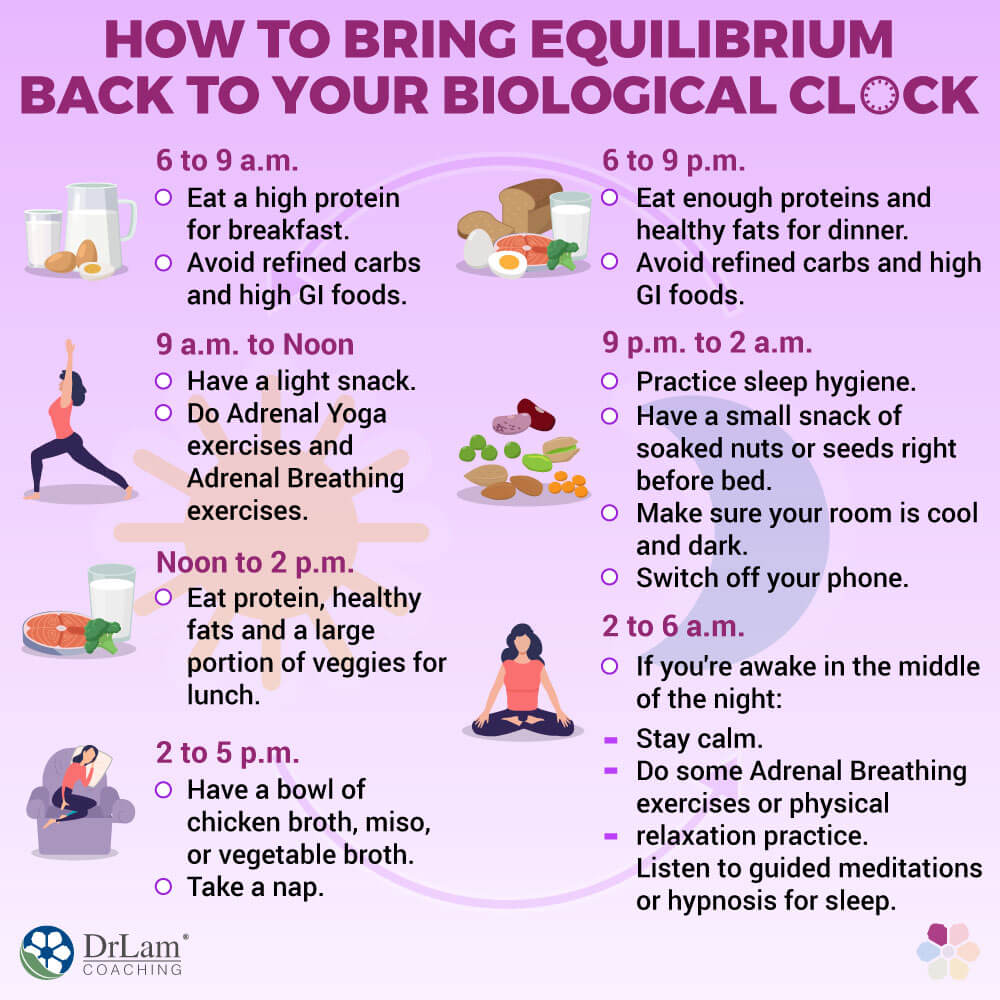

There are seven phases of the circadian rhythm that take place within 24-hours, and bringing back balance to your biological clock has to take these phases into account, with specific steps taken for each phase to help mimic what would naturally occur if there was no disruption.

A protocol of different foods, supplements, and practices applied strategically at the right times can bring about balance once again to your biological clock, though, depending on how out of sync it’s been, it may take several months to work.

The different phase protocols are summarized below, but it’s recommended that you follow the guidance of an experienced practitioner, especially if your HPA axis markers are significantly dysregulated or if you are in the advanced stages of AFS.

A healthy person with a balanced biological clock should wake up feeling refreshed after a good night’s sleep and get a boost of energy right after. Your HPA axis markers should start out low upon waking, rise to their highest levels an hour afterward, then come down again.

A healthy person with a balanced biological clock should wake up feeling refreshed after a good night’s sleep and get a boost of energy right after. Your HPA axis markers should start out low upon waking, rise to their highest levels an hour afterward, then come down again.

If they are already high, that means your body was in fight or flight mode during the night and you probably wake up feeling wired and tired. In this case, working on phase six and seven, that we’ll discuss below, can help with this. Also, meditation upon waking can help bring already high levels down.

If your HPA axis markers are low upon waking, as they should be, but then don’t rise afterward, your body won’t get the jump-start it needs and your immune system won’t reset. You also probably wake up feeling tired and won’t get an energy boost to help you through the day. In this case, you need to work on the Awakening Rhythm phase.

Start with a good breakfast that has a lot of protein. Stay away from refined carbs and high glycemic index foods so that your blood sugar doesn’t spike then crash. Do Adrenal Circulation and Adrenal Restorative exercises. Supplements that can help restore this phase and give you more energy in the morning include DHEA, glutathione, iodine, zinc, selenium, glycine, pregnenolone, arginine, thyroid glandulars, adrenal glandulars, and vitamins B5, B6, B12, C, and D. However beware of taking too many stimulating glandulars if you are in advanced stages of adrenal fatigue as it may have paradoxical effects and actually worsen your outcome if they have the wrong timing.

For healthy individuals, that energy boost that resulted from eating breakfast and the spike in cortisol, norepinephrine, and adrenaline should be enough to sustain them until lunchtime. But for those with adrenal fatigue and dysregulated HPA axis markers, even if you eat a good breakfast and take supplements, you may start to lose energy again, and you can end up with a hypoglycemic episode.

This is where a lot of people are in danger of overdoing it with stimulants like coffee or succumbing to sugar cravings. Instead, have a light snack now to help maintain blood sugar levels and prevent metabolic disruption, focusing on nutritionally dense rather than refined or sugary foods. You can also do Adrenal Yoga exercises and Adrenal Breathing exercises. These can help bring down any excess HPA axis markers still left over from the spike in the morning.

Herbs and supplements that can support this phase include magnesium, fish oil, GABA, 5-HTP, fermented milk thistle, theanine, activated charcoal, bacopa, and lipoic acid. Biofeedback therapy that is composed of different calming and relaxation techniques can also be useful now to help reduce neurotransmitter excitation.

If you’ve followed the recommendation of the first two phases, ideally you will arrive at lunch feeling fresh and energized, hungry enough to eat but not too hungry to binge. The biggest risk at this point is to eat too much or to eat the wrong kinds of foods so that you end up in a food coma, which will then link straight into the afternoon energy slump, making you sluggish for a solid four to five hours.

If you’ve followed the recommendation of the first two phases, ideally you will arrive at lunch feeling fresh and energized, hungry enough to eat but not too hungry to binge. The biggest risk at this point is to eat too much or to eat the wrong kinds of foods so that you end up in a food coma, which will then link straight into the afternoon energy slump, making you sluggish for a solid four to five hours.

To avoid this, eat a lunch whose calories come mainly from protein and healthy fats and a large portion of greens or other veggies. A big salad with grilled chicken or salmon is an excellent choice. Try not to drink liquid half an hour before lunch and an hour after lunch so that your stomach acid is not diluted and you digest your lunch properly. You should also avoid caffeine, stress, and intense exercise in this phase. Taking a short walk and a nap would be ideal if your circumstances allow.

This is when many people experience the dreaded afternoon slump, and where many give in to quick fixes of drinking another cup of coffee (or two), having an energy drink, eating sweets, and then of course suffering the consequences, such as an excess release of HPA axis markers, blood sugar spikes and crashes, anxiety, and adrenal crashes.

Another possible culprit could be dehydration and low sodium levels in the body, and it can be a little tricky to address both simultaneously since it requires you to hydrate with water, which can dilute the sodium levels in the body. A simple fix for this is having a bowl of miso or vegetable broth, or adding a dash of salt to your water bottle. If you have adrenal fatigue, your sodium to potassium ratio won’t be balanced, and so it can help to eat fewer potassium-rich foods and add a little bit of salt to your diet and water.

Herbs and supplements that can support this phase include some of the ones previously mentioned, such as arginine, DHEA, pregnenolone, and magnesium. Other helpful herbs and supplements for this phase include chromium, holy basil, glutamine, hydrolyzed collagen type 1 and type 3, and marine phytoplankton.

If you were not able to take a nap after lunch but you can now, it is a good idea. One thing to remember when dealing with AFS or dysregulation in metabolism, the NEM stress response, the HPA, or any other imbalance is that during recovery, your body is in need of rest. It’s not a bad thing to give it what it needs; it doesn’t mean that you will have to keep taking naps and rest this much once your health is doing better.

This is the phase right before sleeping, and your HPA axis markers should be winding down and allowing your body to calm down even more. You still need to have dinner, especially if you’re recovering from adrenal fatigue, so that you don’t get a hypoglycemic episode during the night and to keep your energy and nutrient stores replenished.

Again, stay away from refined carbs and high glycemic index foods, eat a little lighter than during the day, and have enough proteins and healthy fats to sustain you throughout the night so you don’t wake up with low blood sugar or get midnight cravings. Try to limit your liquid intake after dinner so you don’t need to disrupt your sleep to use the bathroom.

Supplements that can support this phase include chromium, 5-HTP, fish oil, magnesium, and GABA in low doses. You can also try taurine and theanine.

After dinner, take some time to relax, read, stretch, and spend time with family. Try to stay away from digital devices and overstimulation, such as watching TV or reading the news. If you must use digital devices, use a blue-light blocking filter on their screens or wear blue-light blocking glasses. Meditation and biofeedback techniques can be useful again now to help bring down excitatory HPA axis markers to allow your body to slow down.

This is when sleep hygiene routines will have the biggest impact. For a healthy individual, cortisol, norepinephrine, and adrenaline levels drop, and acetylcholine takes over as the main neurotransmitter for the peripheral nervous system. This allows the body to enter the “rest and digest” phase and for all the different repairs to take place. It is essentially the opposite of the “fight or flight” mode.

You can have a small snack of soaked nuts and seeds right before bed to keep blood sugar levels stable. If you have low cortisol levels, licorice and grapefruit juice can help, but if your cortisol levels are high, take bioactive milk peptides at bedtime. You can also try phosphatidylserine a few hours before bed and again right at bedtime.

You can have a small snack of soaked nuts and seeds right before bed to keep blood sugar levels stable. If you have low cortisol levels, licorice and grapefruit juice can help, but if your cortisol levels are high, take bioactive milk peptides at bedtime. You can also try phosphatidylserine a few hours before bed and again right at bedtime.

To get the best quality sleep, make sure your room is cool and dark and your phone is switched off. Don’t turn on the lights if you need to use the bathroom at night - opt for night lights instead. If you suffer from sleep onset insomnia, which many people do, the supplements already listed will help, along with niacin, passionflower, melatonin, progesterone, and valerian root.

This is when you should be fast asleep, and your body ideally has enough inhibitory neurotransmitters to keep any excitatory neurotransmitters, like adrenaline or norepinephrine, under control. But if you have AFS, you may find yourself able to fall asleep but unable to stay asleep, and you may be waking up around 2 or 3 a.m. and having a hard time falling back asleep. This is called sleep maintenance insomnia.

If you have taken all the steps outlined above during the day and especially right before bed, you have a much better chance at sleeping through the night and reaping the benefits of a good night’s sleep. Some of the supplements and herbs already listed but taken in time-release form could be more useful for sleep maintenance insomnia since they will keep slowly working while you sleep. Also, taking the right supplements at the right time will make all the difference.

If you still do end up awake in the middle of the night, although it is frustrating and is detrimental for health, try to stay calm. You can do some Adrenal Breathing exercises, other biofeedback techniques, or some kind of physical relaxation practice. Listen to guided meditations or hypnosis for sleep, and then adjust your routine the next day according to what worked and what didn’t work for you this time around.

Most of the suggested herbs and supplements above need to be taken in certain amounts, at the right time of day, or they can cause undesirable fluctuations in your HPA axis markers. That’s why we don’t suggest you try any of these supplements and herbs out by yourself, since you may end up overdoing it, or not doing it correctly. The result can be either ineffectiveness or paradoxical reactions, which are common in adrenal fatigue. An experienced professional who understands your specific condition and needs can help you with this complicated process.

Be patient as you recover, it takes months and even years to develop these imbalances in HPA axis markers and circadian rhythm, so it’s normal that it takes a few months to restore balance. But balance is possible, as is optimal health, well-being, and a good quality of life.

© Copyright 2020 Michael Lam, M.D. All Rights Reserved.

HPA axis markers are hormones and neurotransmitters that are secreted when the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is activated. They include cortisol, adrenaline, and norepinephrine. Measuring them can help you understand what’s going wrong with your biological clock and give you clues on how to bring it back to balance.