Mitral valve prolapse syndrome, chronic orthostatic intolerance, and orthostatic tachycardia symptoms are each names that reference postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). POTS is not a new illness. It is caused by a malfunction of the patient's autonomic nervous system (ANS).

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) governs the involuntary inner workings of our body through five separate but related branches. They control functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, temperature control, bladder control, sweating, and the fight-or-flight response to stress. The two most famous branches are called the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). The ANS branch is regulated by neurotransmitters and hormones like dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine (also called adrenaline) and acetylcholine. Any illness caused by dysfunction of the ANS is collectively called dysautonomia.

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) governs the involuntary inner workings of our body through five separate but related branches. They control functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, temperature control, bladder control, sweating, and the fight-or-flight response to stress. The two most famous branches are called the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). The ANS branch is regulated by neurotransmitters and hormones like dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine (also called adrenaline) and acetylcholine. Any illness caused by dysfunction of the ANS is collectively called dysautonomia.

POTS is a subset of dysautonomia where orthostatic (blood pressure) intolerance is associated with the presence of excessive tachycardia (fast heart rate) on standing. It is believed to be caused by central hypovolemia.

Between 75 and 80 percent of POTS patients are female and of menstruating age. Most male patients develop POTS in their early to mid-teens during a growth spurt or following a viral or bacterial infection. Some women develop POTS or tachycardia symptoms with pregnancy.

When lying down, 25 percent of our blood lies in our chest cavity. Upon standing, 500-1000 cc of blood is pulled from our chest to the abdomen and legs by gravity. To maintain adequate blood profusion to our brain and prevent fainting, the SNS is automatically activated, with norepinephrine released by the brain. This hormone travels to the heart and peripheral blood vessels, narrowing blood vessels and increasing the heart rate. Blood flow to the brain is increased. Without norepinephrine, one simply cannot maintain an upright position for long in day-to-day living. Many of the POTS or tachycardia symptoms come from this inability to move the blood quickly to the brain.

Epinephrine, another hormone, also plays a part in normal daily life, though in a much lesser degree. It is primarily released when the body is under severe stress. As part of the fight-or-flight response, epinephrine is the body’s last response to stress. It acts to supply blood to brain and muscle in order for us to survive. It is under the control of the adrenomedullary hormone system.

SNS activation in normal people causes the normal heart rate to increase transiently by 10-15 beats per minute along with a very slight increase in blood pressure on standing. Instantly, an automatic vessel dilatation occurs and blood pressure and heart rate returns to normal. In some people, these activation and feedback mechanisms fail, altering the first increase in profusion and subsequent normalization of blood to the heart and brain. This is when the POTS and tachycardia symptoms surface. Blood pressure falls (orthostatic intolerance), with a compensatory rise in heart rate (tachycardia) when it is too fast.

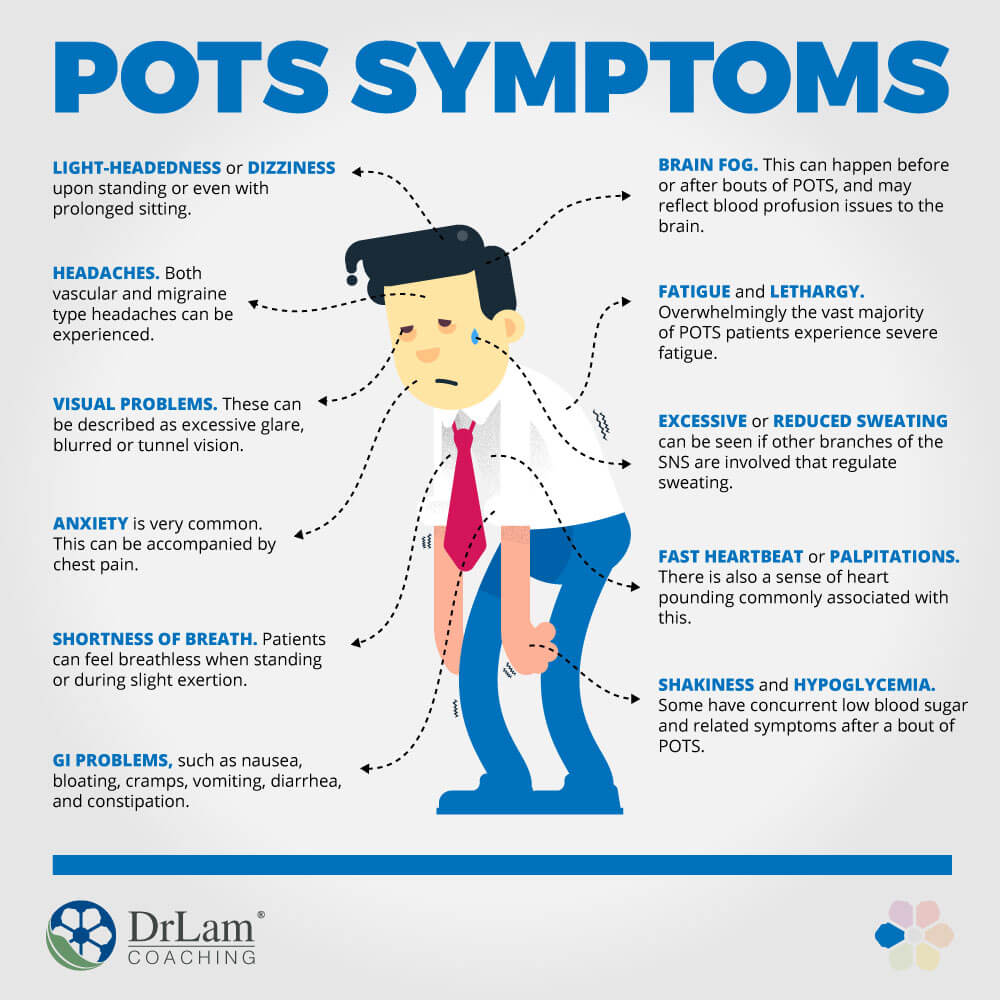

Remember that as a syndrome, POTS is a collection of symptoms. The symptoms are widespread throughout the body because of the all-encompassing effect of the ANS internally. No organ system can fully escape. You don’t need to have all the symptoms to be diagnosed. They can include:

If your doctor suspects POTS, a tilt table test is ordered. You lay down on a table, which is then tilted while cardiovascular biomarkers are measured. In adults, POTS is clinically diagnosed when there is a heart rate increase of 30 beats per minute (bpm) or more from baseline, or over 120 bpm within the first 10 minutes of standing in an upright position. Unfortunately, many times the results can be inconclusive or borderline.

If your doctor suspects POTS, a tilt table test is ordered. You lay down on a table, which is then tilted while cardiovascular biomarkers are measured. In adults, POTS is clinically diagnosed when there is a heart rate increase of 30 beats per minute (bpm) or more from baseline, or over 120 bpm within the first 10 minutes of standing in an upright position. Unfortunately, many times the results can be inconclusive or borderline.

While the diagnostic criteria of POTS focuses on the abnormal heart rate increase upon standing, sufferers usually present with a wide set of symptoms beyond blood pressure and rate irregularities. Some POTS patients have no blood pressure dysregulation on standing. Many have high levels of plasma norepinephrine while standing, reflecting increased SNS tone. Norepinephrine acts on the brain and triggers anxiety.

Remember that a person with POTS is stressed every time she/he moves or stands. There is a constant over-release of epinephrine and norepinephrine. It is for this reason that POTS is so often misdiagnosed as anxiety.

The key to proper diagnosis of POTS should factor in the many possible associated symptoms to form a complete clinical picture of an overall autonomic nervous system in disarray.

As with any syndrome, the continuum of dysfunction varies from mild to severe. Those with mild symptoms lead normal lives. In severe cases, even mundane daily activities such as eating, walking, and bathing can be problematic.

Approximately 25 percent of POTS patients are disabled and unable to work.

Illnesses frequently associated with POTS include fibromyalgia, viral illness, autoimmune disease, adrenal disorders, mast cell disorders, hypersensitivity of baroreceptors, chronic fatigue syndrome, post traumatic stress disorder, panic attacks, inappropriate sinus tachycardia, irritable bowl syndrome, type 1 diabetes, Lyme disease, and mitochondrial diseases. This is clearly a complicated and convoluted disorder because of the widespread effect of the ANS in the body.

To better describe the pathophysicology of POTS, it can be grouped in various ways, such as primary (unknown cause) and secondary (caused by something else) POTS, hypovolemic POTS (associated with low blood volume), partial dysautonomic POTS (associated with a partial autonomic neuropathy), and hyperadrenergic POTS (associated with high levels of norepinephrine).

About 20-30 percent of POTS patients fall into this group. It is characterized by a high normal level of plasma norepinephrine in the supine position, while the upright norepinephrine is usually elevated (>600 pg/ml). As the name implies, it is caused by an uptight sympathetic nervous system. In some subjects, this hyperadrenergic response may be a compensatory reaction to either hypovolemia or peripheral dysautonomia with venous pooling.

Hyperadrenergic POTS has a strong familial link, and is associated with light sensitivity, stress intolerance, adrenergic urtricia, and medication sensitivities.

There is a strong link between hyperadrenergic POTS and Adrenal Fatigue Syndrome (AFS).

Treatment of POTS should be directed at the underlying cause as the top priority and long-term solution. Unfortunately, root causes usually evade detection without a very detailed history. Most physicians trained in Western medicine tend to focus on symptoms control as follows:

Increase fluid intake to support volume and adrenal function

Increase fluid intake to support volume and adrenal function

Use of firm compression support socks (compared to mild compression socks, for varicose veins) can avoid blood pooling in lower extremities.

Avoidance of diuretics such as coffee, tea and medications with that effect.

Focus on reclining exercises such as rowing instead of upright exercise such as running.

Prescribe medications such as Fludrocortisone, Adderall, Pyridostigmine, Benzodiazepines, Beta Blockers, ProAmitine (Midodrine), and Clonidine, SSRIs such as Prozac or Zoloft, and Dexedrine. In severe cases, Florinef may be considered. Beta blockers and calcium channel blockers can be used to reduce a high resting heart rate.

Adrenal Fatigue Syndrome (AFS) is a neuroendocrine condition induced by stress that can be physical or emotional. There are four stages, with symptoms ranging from mild to severe. Fatigue is the hallmark symptom and can be incapacitating. Symptoms of advanced AFS include reactive hypoglycemia, heart palpitations, lightheadedness or dizziness on arising, insomnia, fatigue, salt craving, brain fog, and low blood pressure. The presence of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome or POTS disease can further complicate the individual's health.

Adrenal Fatigue Syndrome (AFS) is a neuroendocrine condition induced by stress that can be physical or emotional. There are four stages, with symptoms ranging from mild to severe. Fatigue is the hallmark symptom and can be incapacitating. Symptoms of advanced AFS include reactive hypoglycemia, heart palpitations, lightheadedness or dizziness on arising, insomnia, fatigue, salt craving, brain fog, and low blood pressure. The presence of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome or POTS disease can further complicate the individual's health.

When the body perceives a threat to survival, it releases anti-stress hormones, including cortisol, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. If external stressors are not removed, continued release leads to a body chronically overloaded with norepinephrine in what is known as sympathetic overtone. In other words, the body is bathed in a sea of norepinephrine in order to keep the brain on high alert and the heart ready to run away or face danger. Sufferers of advanced AFS are therefore often in a constant alarm state as part of the body’s automatic response to stress.

While norepinephrine’s purpose is to ensure our survival, there are unintended negative consequences when produced in large quantities over time. The cardiovascular system is particularly at risk.

A quick comparison with the most cardiovascular related symptoms of POTS disease mentioned earlier shows many commonalities with advanced stages of AFS. Both tie to and are largely the result of excessive norepinephrine. Specifically, hyperadrenergic POTS disease is associated with elevated levels of norepinephrine, and so is advanced AFS; where chronic stress triggers excessive outpouring of norepinephrine as part of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation stress response.

Excessive norepinephrine in the brain acts as a potent stimulatory neurotransmitter. It puts the brain in a state of high alert and keeps us mentally sharp on the look-out for danger. We feel wired, unable to relax. Sleep is a low priority in such a situation as far as the body is concerned. Falling asleep is a challenge unless physically exhausted. Many require sleep aids and even medications just to fall asleep. After a few hours of rest, the body automatically awakens, and is unable to fall asleep again. Sometimes this is also accompanied by heart palpitations. During the day, a sense of nervousness and anxiety may be present.

Norepinephrine also acts outside the brain as it travels as a hormone to the heart, increasing the heart rate as well as the force of the heartbeat. A pounding heart rate is largely the result of excessive norepinephrine.

Constant overload of norepinephrine, sympathetic overtone, can contribute or lead to hyperadrenergic POTS mentioned earlier, with symptoms mimicking it on a subclinical or clinical basis.

In the case of advanced AFS, there is an additional aggravating factor of hormonal overload, and it has to do with epinephrine, norepinephrine’s chemical daughter. Epinephrine is the strongest of all emergency hormones. It is similar in action to norepinephrine, but much more potent. It is responsible for the flight-or-fight response and is the body’s hormone of last resort when dealing with stress. When the body’s norepinephrine level is high, part of it is automatically converted to epinephrine, leading to a higher epinephrine level. Epinephrine also acts on the cardiovascular system as norepinephrine, but stronger. The negative effects of epinephrine on the cardiovascular system are compounded.

In the case of advanced AFS, there is an additional aggravating factor of hormonal overload, and it has to do with epinephrine, norepinephrine’s chemical daughter. Epinephrine is the strongest of all emergency hormones. It is similar in action to norepinephrine, but much more potent. It is responsible for the flight-or-fight response and is the body’s hormone of last resort when dealing with stress. When the body’s norepinephrine level is high, part of it is automatically converted to epinephrine, leading to a higher epinephrine level. Epinephrine also acts on the cardiovascular system as norepinephrine, but stronger. The negative effects of epinephrine on the cardiovascular system are compounded.

Furthermore, in cases of severe stress, a branch of the autonomic nervous system called the adrenomedullary hormonal system is activated. Epinephrine is released directly from inside the adrenal glands in an area called the adrenal medulla when this system is activated.

Epinephrine is called the body’s hormone of last resort for good reason. It is the most powerful hormone in the body in terms of potency, and has no opposing hormones once released. Epinephrine released from the adrenal medulla travels to the heart and leads to a fast heart rate in order to deliver more blood to the brain. It works along-side norepinephrine, but is more powerful. Reactive sympathetic response is the term we use to describe a body bathed in a sea of epinephrine with its negative side effects.

It comes as no surprise that those in advanced stages of AFS often have symptoms mimicking POTS disease. Unfortunately, this is seldom recognized.

Ellen is a 35-year-old adrenal fatigue sufferer in advanced stages. She has been struggling with fatigue and lethargy for about ten years, and has been under the care of seven doctors over this time. It started with a stressful workload and relationship problems. Her fatigue was mild at first, but gradually worsened. In the past few years, she began to experience lightheadedness on arising along with a fast heart rate, as well as salt cravings and low blood pressure at rest. She used to be a very active person but now spends much of her free time resting. She is barely able to hang on to her job, and feels that it is in jeopardy because of frequent absenteeism in recent years. When she is severely stressed, she feels palpitations and a fast heart rate, even at rest. These symptoms are accompanied by anxiety, headache, shortness of breath, and hypoglycemia. She goes on numerous visits to the emergency room as a result. Cardiac workup is invariably normal and she is sent home with anti-anxiety agents. She saw an endocrinologist who ordered a tilt table test but the result was inconclusive. All other laboratory tests are normal. Her fatigue continues to worsen with time, and energy crashes are more prominent and frequent. Her doctor also gave her an ACTH test that showed unremarkable levels. She was told her adrenal glands are normal.

Ellen’s quality of life is severely restricted. She does not have the energy for regular exercise or dance. She has to get up slowly in order not to feel dizzy. She is easily startled with loud sounds. She cannot tolerate long exposure to direct sunlight, and she gets dehydrated easily. During the day, she feels anxious, and at night, wired and tired. Falling asleep can take an hour or more. She is dependent on sleep medicine to fall asleep, however, she wakes up in the middle of the night unable to go back to sleep. She gets up in the morning feeling lethargic and unrefreshed.

Ellen’s quality of life is severely restricted. She does not have the energy for regular exercise or dance. She has to get up slowly in order not to feel dizzy. She is easily startled with loud sounds. She cannot tolerate long exposure to direct sunlight, and she gets dehydrated easily. During the day, she feels anxious, and at night, wired and tired. Falling asleep can take an hour or more. She is dependent on sleep medicine to fall asleep, however, she wakes up in the middle of the night unable to go back to sleep. She gets up in the morning feeling lethargic and unrefreshed.

Her doctor told her she is borderline POTS disease and wants to start her on medication. She wants to pursue a more natural solution to her problem.

Any astute clinician must consider AFS as a secondary cause of POTS disease if the history of the patient has an indication or history of physical or emotional stress. This includes a history of excessive exercise, infection, surgery, accident, overwork, relocation, divorce, or relationship problems. Frequent visits to the emergency room complaining of chest pain, palpitations and anxiety but accompanied by negative cardiac workup in a setting of stress is a classic alert.

Treatment for POTS disease by conventional medicine could help alleviate some of the symptoms. For long-term recovery, the focus should be on removing the underlying stressors and healing the adrenals. Once the adrenals are healed, symptoms of POTS disease automatically and spontaneously resolve. It can happen in a short time.

One should be careful not to begin heart rate suppression medication too early. Such a move could potentially force the heart to seek alternative electrical conduction pathways over time that can create a deeper set of problems while the underlying cause is being masked. One should also avoid anti-anxiety agents and antidepressants unless they are for temporary use, as these also tend to mask underlying problems.

If your AFS is mild (stages 1 and 2) and you have symptoms of POTS disease that are not debilitating or prevent you from carrying out your active daily living, you can consider vitamin C, the B vitamin pantothenate, the amino acid l-tyrosine, licorice, maca, green tea, ginseng, ashwagandha, and adrenal gland extracts. They support healthy adrenal function, strengthen blood vessel constriction, and increase heart function. Because many of these are stimulatory in nature, always pay attention to the delivery system to ensure bioavailability and avoid over-dosage. Side effects include jitters, addiction, cramps, brain fog, and tremors. This is especially true if the dosage does not match the body’s need.

Those with advanced AFS (stages 3 and beyond) and symptoms of POTS disease that are troublesome to the degree of interfering with normal living should not embark on any nutritional supplement program without careful consideration and a master recovery plan in place. One should proceed with extreme caution because a body with advanced AFS is thus far most likely in a state of hypersensitivity by the time POTS disease, either clinically or subclinically, is present. They are also at risk of paradoxical reactions and a low threshold for adrenal crashes. Their extracellular matrix is often congested, and the liver overburdened. Energy level is very low. Attempts to stimulate the adrenals and cardiovascular system using supplements that may have worked in earlier stages of AFS may backfire. Even a small amount of these vitamins, such as vitamin C or B, ashwagandha, rhodiola, maca, licorice, and glandulars can make POTS disease worse and trigger adrenal crashes.

Those with advanced AFS (stages 3 and beyond) and symptoms of POTS disease that are troublesome to the degree of interfering with normal living should not embark on any nutritional supplement program without careful consideration and a master recovery plan in place. One should proceed with extreme caution because a body with advanced AFS is thus far most likely in a state of hypersensitivity by the time POTS disease, either clinically or subclinically, is present. They are also at risk of paradoxical reactions and a low threshold for adrenal crashes. Their extracellular matrix is often congested, and the liver overburdened. Energy level is very low. Attempts to stimulate the adrenals and cardiovascular system using supplements that may have worked in earlier stages of AFS may backfire. Even a small amount of these vitamins, such as vitamin C or B, ashwagandha, rhodiola, maca, licorice, and glandulars can make POTS disease worse and trigger adrenal crashes.

Consider the following:

POTS disease can be a very serious condition. Symptoms tend to occur in those in advanced stages of AFS when the body is flooded in a sea of norepinephrine and epinephrine. Frequent visits to the emergency room with complaints of heart palpitations amidst a negative cardiac workup are the norm.

AFS is perhaps the most commonly overlooked secondary cause of hyperadrenergic POTS disease. Quickly beginning a comprehensive adrenal fatigue recovery plan should be the priority. A recovery plan is required for long-term success to prevent POTS disease from recurring.

As the adrenals heal, one should notice that the frequency and intensity of POTS disease subsides. This can happen in a short time, especially for those who are young and have good rebound capabilities.

That can happen to some people, especially those with circulation issues. If that happens, skip those poses. Also, find out from your doctor why you have dizziness during those poses.